Using Xyloglucan Oligosaccharides as Biostimulant to Enhance Tobacco Tolerance to Salt Stress- Juniper Publishers

Journal of Agriculture Research- Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Xyloglucan oligosaccharides (XGOs) derived from the

hydrolysis of plant cell wall xyloglucan, are a new class of naturally

occurring biostimulants that exert a positive effect on plant growth and

morphology and can enhance plant’s tolerance to stress. Here, we aimed

to determine the influence of exogenous Tamarindus indica L. cell

wall-derived XGOs on Nicotiana tabacum’s tolerance to salt stress by

examining the plant’s morphology, physiological, and metabolic changes

after XGO application. N. tabacum plants were grown in solid media for

two months under salt stress with 100mM of sodium chloride (NaCl) ±

0.1μM XGO. Germination percentage (GP), number of leaves (NL), foliar

area (FA), primary root length (PRL), and density of lateral roots (DLR)

were measured. Also, 21-old-day N. tabacum plants were treated with a

salt shock (100mM NaCl) ± 0.1μM XGOs. Proline, total chlorophyll, and

total carbonyl contents in addition to lipid peroxidation degree and

activities of four enzymes related to oxidative stress were quantified.

Results showed that under saline conditions, XGOs caused a significant

increase in NL and PRL, promoted lateral root formation, produced an

increase in proline and total Chl contents, while reducing protein

oxidation and lipid peroxidation. Although they modulated the activity

of the enzymes analyzed, they were not statistically different from the

salt control. XGOs may act as metabolic inducers that trigger the

physiological responses for counteracting the negative effects of

oxidative stress under saline conditions.

Keywords: Antioxidant system; Biostimulants; Nicotiana tabacum; Salt stress; Xyloglucan oligosaccharides

Abbreviations: CAT:

Catalase; Chl: Chlorophyll; DLR: Density of Lateral Roots; FA: Foliar

Area; GP: Germination Percentage; GPX: Peroxidase; GR: Glutathione

Reductase; MS: Murashige and Skoog; NaCl: Sodium Chloride; NL: Number of

Leaves; PCA: Principal Component Analysis; PRL: Primary Root Length;

RL: Lateral Roots; ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; SOD: Superoxide

Dismutase; XGOs: Xyloglucan Oligosaccharides

Introduction

Modern agriculture faces many challenges in order to

meet the growing demand for worldwide food. The world’s population is

growing at an accelerated rate. By the end of 2050 it is expected to

reach 9.8 billion people and 11.2 billion in 2100 according to the

“World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision”, published by the United

Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. However, food

productivity and availability are decreasing as a result of the effects

of several biotic and abiotic factors. Therefore, several actions are

being taken to reduce these losses and to cope with the growing food

need for the world’s population.

Soil salinity is a worldwide phenomenon that occurs

under almost all climatic conditions and is a major impediment to

achieving increased crop yields. Using the FAO/UNESCO soil map of the

world (1970–1980), FAO estimated that 19.5% of irrigated land were

salt-affected soils, and of the almost 1.5 billion ha of dryland

agriculture, 32 million (2.1%) suffer from salinity problems [1].

Salt-affected soils are characterized by abundant quantities of neutral

soluble salts that adversely affect plant uptake of nutrients in the

soil and their growth [2]. Under salt stress, plants are also under

other types of stresses, which have deleterious effects on them such as

water stress, ionic toxicity, and nutritional deficiencies

[2]. Altogether, these conditions confer oxidative stress and

metabolic imbalance to plants [3]. Consequently, plants exposed

to high saline conditions shown growth inhibition or retardation.

The morphology of plants exposed to salinity can be affected

by soil salt concentrations, type of plant species, age, and plant

stages (vegetative or flowering), and/or the type of salt present

[4,5]. For example, there is a decrease in plant lengths, leaf (foliar)

areas, leaf numbers and root systems under high concentrations

of NaCl [4]. Also, many studies confirm the inhibitory effects of

salinity on photosynthesis by changing chlorophyll content thus

affecting Chl components and damaging the photosynthetic apparatus

[5].

In addition, plants exposed to high NaCl concentrations (such

as100-200mM) show rapid overproduction of reactive oxygen

species, which have detrimental effects on the plants’ cells. ROS

causes membrane lipid component peroxidation and oxidation of

cellular components such as proteins and nucleic acids, which finally

lead to programmed cell death [6,7]. ROS-initiated damage

is reduced and repaired by a complex antioxidant system, which

combines enzymatic and non-enzymatic components. It consists

of low molecular weight antioxidant metabolites, including ascorbic

acid, carotenoids, glutathione, α-tocopherol and enzymes such

as catalase, peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione reductase

and others. The degree of cellular damage will depend on the

balance between ROS production and elimination by the antioxidant

scavenging system [8].

Plants also accumulate compatible solutes in response to salt

stress, which provides protection to them by participating in ROS

detoxification and cellular osmotic regulation in addition to contributing

to enzyme/protein stabilization and membrane integrity

protection [6]. Among them, proline is one of the most important

ones due to its multiple roles as part of the plant’s response to

various types of stresses. It functions as an osmolyte for osmotic

adjustment, buffering cellular redox potential under stress conditions,

maintaining protein integrity, enhancing different enzymes

activities, and free radical scavenging [9,10]. Its accumulation in

leaves under salt stress has been correlated with stress tolerance

in many plant species, allowing them to survive under this type of

stress [6].

Many efforts have been done to overcome the problems associated

with high soil salinity and salt stress in plants. However,

the use of traditional physical and chemical methods for environmental

restoration of salt contaminated soils demand significant

investment of technological and economic resources [11]. In addition

to these traditional approaches, different biostimulant classes

have been used to increase crop performance under salt stress and

to mitigate stress-induced limitations [12-14]. A plant biostimulant

is any substance or microorganism that is applied to plants

with the aim of enhancing nutrition efficiency, abiotic stress tolerance

and/or crop quality traits regardless of its nutrients content.

By extension, they also designate commercial products containing

mixtures of such substances and/or microorganisms [15]. Plant

biostimulants based on natural materials have received considerable

attention by both the scientific community and commercial

enterprises. According to Stratistics Market Research Consulting

(MRC), the Global Biostimulants Market is accounted for $1.50

billion in 2016 and is expected to grow gradually to reach $3.79

billion by 2023 due to growing importance for organic products

in agricultural industries [16]. However, understanding the mechanisms

by which biostimulants act is critical to their widespread

use for helping plants cope in saline-affected soils.

XGOs, derived from the breakdown of xyloglucans in plant

cell walls, are emerging as a new class of naturally occurring biostimulants

as a result of their positive effects on plant growth and

morphology [17-19]. Plant-derived XGOs are also used as biotic

pesticides and seed coating agents to maintain plant freshness in

addition to capsule materials for synthetic seeds [20]. Xyloglucan

is the quantitatively predominant hemicellulosic polysaccharide

in the primary walls, which consists of ~20% (w/w) dicot and

~5% monocot primary cell walls [21]. Its backbone is composed

of a β-(1,4)-D-glucan backbone that is quasi-regularly substituted

with α-D-xylosyl residues linked to glucose through the O-6 position.

In many species, the backbone has a regular pattern of three

substituted glucose units followed by an unsubstituted glucose

residue [22]. As a variety of complex structures can be formed, a

code letter for each glucosyl residue has been defined to allow for

the unambiguous naming of xyloglucan oligosaccharides. For example,

XGOs can be classified as the XXXG-type of the XXGG-type,

in which a capital G represents a unbranched Glcp residue and a

capital F represents a Glcp residue that is substituted with a fucose-

containing trisaccharide [23]. Soluble XGOs can be obtained

from tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) seeds after partial digestion

with cellulase. A fraction of these XGOs have been shown to have

physiologically active functions in plants and oligosaccharides,

also known as oligosaccharins [19,24]. Their biological properties

in plants depends on the fragmented structures and their concentrations,

which need to be extremely low to get a variety of effects

(10–9 - 10–8M) [17-19]. Few experimental data are available concerning

the use of the XGOs as plant biostimulants for mitigating

the damage imposed by salt stress conditions in plants [25]. Also,

each new formulation requires a new biological evaluation to ensure

that the effects are beneficial, consistent, and predictable.

For all of the above, the objective of this study was to determine

the biostimulating effects of application of exogenous XGO

derived from T. indica L. cell walls on N. tabacum seedlings grown

under saline stress conditions with special attention to their influence

on plant morphology, necessary physiological and metabolic

changes to overcome stress, ROS detoxification, and antioxidant

capacities.

Materials and Methods

Oligosaccharin composition and concentration used

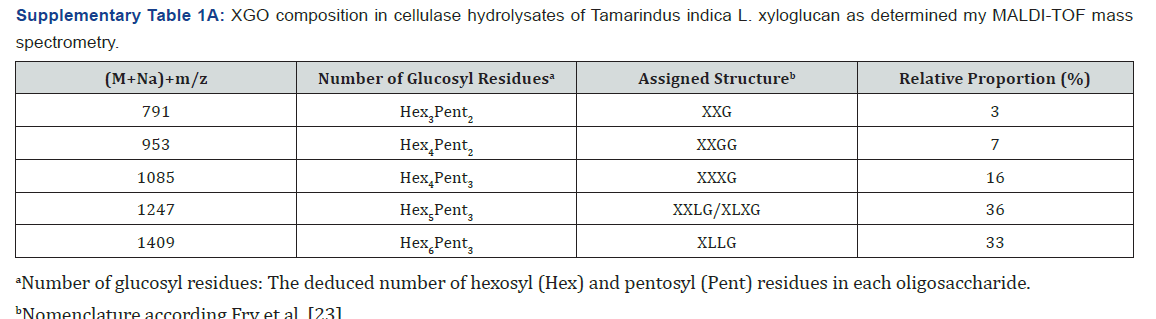

The XGO fraction used in this work was the same formulation

previously reported and tested on plants [18,26]. Briefly, XGO was extracted and purified from tamarind (T. indica L.) seeds.

The predominant composition of the XGO extracts consisted of

XLLG and XXLG/XLXG with lower proportions of XXXG, XXGG, and

XXG oligosaccharides as classified by Fry et al. [23]. Mass spectra

obtained by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation-time of

flight (MALDI-TOF) spectrometry [27] are shown in Supplementary

Table 1&1A. Relative proportions of xyloglucan oligosaccharides

obtained by MALDI and high-performance anion-exchange

chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection analysis

were similar (data not show). The isolated XGO fraction showed

no cellulase activity, and protein could not be detected. The uniformity

of the XGO mixture was confirmed by gel filtration analysis

through a BioGel P2 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA,

USA). XGOs were used at a final concentration of 0.1μM which was

selected based on previous experiments as an optimal concentration

for stimulating root and leaf development in N. tabacum

without causing changes in plants’ chromosome number [17,28].

Plant material and general growth conditions

Botanical seeds of N. tabacum Linn. were used as the plant

model. Seeds were kindly provided by Dr. Alexis Acosta Maspons

from the Institute of Biotechnology of National Autonomous University

of Mexico (UNAM) (Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico). All

seeds were harvested at the same time, kept at 4 °C in the dark,

and grown under the same controlled conditions. Seeds were surface-

sterilized and grown on MS [29] solid medium in a growth

chamber (DAIHAN Scientific, model WISD, Korea) at 23 °C in longday

conditions (16h light/8h dark) and 50% relative humidity.

Sowing and the way in which each treatment was applied was

according to the chosen evaluation (plant and root morphology

measurements and biochemical analysis) and is explained in detail

for each one in this section. Each experiment was repeated to

generate three biological replicates.

Germination percentage and plant morphology measurements

Disinfected seed were sowed onto magenta boxes with MSagar-

media, either alone as a negative control, supplemented with

XGO at 0.1μM or 100mM NaCl to induce salt stress, or a combined

(both NaCl+XGO). The concentration of the NaCl solution was determined

based on experimental data (data not shown) in which

it was considerable biomass decrease in the presence of 100mM

NaCl was demonstrated. Each treatment consisted of nine seeds

per magenta box and five boxes per each biological replicate. Germination

percentage was calculated 10 days after sowing. Germination

criteria were considered complete germination after the

embryo emerged from the seed and a whole seedling was formed

[30]. For plant morphology analysis, seedlings were grown for two

months, and the number of leaves was then counted. Also, leaves

were harvested by cutting three of the oldest ones to measure their

foliar area, which were immediately photographed under a stereomicroscope

(Olympus, Model CX31-RTSF) coupled to an Infinity

Analyzer camera. FA was measured using the Infinity Analyze 3

software (Lumenera) according to the manufacturer instructions.

For root length measurements and lateral root primordium

frequency, sterilized seeds were plated on square Petri dishes in

a vertical orientation containing MS-agar-media as control or supplemented

with XGO at 0.1μM or 100mM NaCl to induce salt stress

or a combination of XGO+NaCl. Each treatment consisted of six

seeds per Petri square dishes and four dishes per each biological

replicate. All measurements were performed on 3-week old plants

that were fixed for 72h as previously described and had exhibited

whole root systems [18]. The total number of lateral roots, which

is the sum of the number of lateral root and number of primordia,

were counted directly under a stereomicroscope (Olympus, Model

CX31-RTSF). The fixed plants were then placed on a slide to allow

the primary root extension and measurements by taking photographs

and processing the images. A microscope (Olympus, Model

SZ2-ILTS) coupled to an Infinity Analyzer camera was used, and

primary roots lengths were measured using the Infinity Analyze 3

(Lumenera) software according to the manufacturer instructions.

Lateral root density (DLR, represented as D in the formula) per

mm of primary root length (PRL, represented as L in the formula)

was calculated using the following equation: D = (RL+P)/L, where

RL + P is the sum of the number of lateral root and number of

primordia [31].

Induction conditions for biochemical analysis

For all of the biochemical analyses, a uniform induction experiment

was designed in order to analyze XGO- (alone or in combination

with salt shock) induced dynamic changes in N. tabacum

seedlings. Specifically, we focused on the restitution phase (stage

of resistance, continuing stress) of plants’ stress response phases

[32]. Consequently, seeds were first placed in magenta boxes containing

MS-agar-media to allow their homogeneous growth for 21

days. After that time, four treatments were administered:

a. One mL of sterile distilled and deionized water as a negative

control.

b. A solution of 100 mM NaCl for salt shock.

c. 0.1μM XGO.

d. 0.1μM XGO+100mM NaCl were added to the top of the solid

media.

Sampling leaves were taken at two and five days after induction,

immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C

until their use.

Quantification of proline and photosynthetic pigment content

After two and five days of XGO application with or without salt

shock using NaCl 100mM, proline and total chlorophyll (Chl a+b)

contents were measured. Proline extractions and quantifications

were performed as previously described [33]. Briefly, the extract

was prepared by mixing 20mg of ground leaves in 1mL of 80%

ethanol, sonicated for 5min, and incubated for another 20min in

the dark. The mixture was centrifuged at 20,000g for 5min, and 200μL of the supernatant were added to 400μL of reaction mix

(ninhydrin 1% (w/v) in acetic acid 60 % (v/v), ethanol 20%

[v/v]), and heated at 95 °C for 20min. Finally, absorbance was determined

at 520nm using a FLU Ostar Omega Microplate Reader

(BMG LABTECH GmbH, Germany). A calibration curve was used

for proline concentration quantification and expressed as μg of

proline per mg of plant fresh weight. For photosynthetic pigment

content quantification, the Chl a and b and total chlorophyll (Chl

a+b) contents were extracted with 80 % acetone and measured as

described elsewhere [34].

Protein and lipid oxidative damage

Plant leaf tissue was ground to a fine powder with liquid nitrogen

to ensure sample homogenization. Protein oxidation was

measured using protein carbonyl content [35]. Briefly, 100μL

of sodium phosphate buffer (PBS, pH 7.8) was added to 400mg

of each sample, sonicated for 20min in the dark, centrifuged at

20,000g during 20min at 4 ºC, and the supernatant was used. Protein

concentration in the supernatant was measured using a BCA

Quantic Pro Sigma Kit to compare carbonyl content related to total

protein content. Total carbonyl content was measured using dinitrophenylhydrazine

(DNPH) reagent [35].

Lipid oxidation was analyzed with a thiobarbituric acid reactive

substances (TBARS) method [36]. For the assay, 200mg of

ground plant sample was submerged in 1000μL of acetone and

sonicated for 5min. The mixture was then incubated for 10min

in the dark and centrifuged at 4 °C and 20,000g for 5min. Then,

200μL of the supernatant was added to 300μL of a reaction mix

containing 2:1 of 20 % (v/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and 0.67%

(w/v) of thiobarbituric acid (TBA). The reaction mix was heated at

95 °C for 15min, cooled at room temperature, and centrifuged at

20,000g at 4 °C for 20min. Lipid oxidation was measured by determining

the absorbance at 532nm using a FLU Ostar Omega Microplate

Reader (BMG LABTECH GmbH, Germany). The methylenedianiline

(MDA) standard and standard curve for the estimation

of total MDA were prepared as previously described [37]. Results

were indicated as A532 per gram of plant sample.

Antioxidant enzyme activities

Plant leaves collected (0.4g) were homogenized in liquid nitrogen

and 100μL of PBS (pH 7.8) containing protease inhibitor

(Sigma Aldrich) concentration 5X. The mixture was then sonicated

for 20 min in the dark and centrifuged at 20,000g at 4 ºC for

20min, after which time the protein content was measured using

a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) Sigma® kit. Enzyme activities were determined

immediately. Activities of the antioxidant enzymes, CAT

(EC EC 1.11.1.6), GPX (EC 1.11.1.7), GR (EC 1.6.4.2, GR), and SOD

(EC 1.15.1.1, SOD) were determined. The evaluation of enzymatic

activities was performed by comparing equal amounts of total

protein extracts from the samples collected.

CAT activity was measured by monitoring the enzyme-induced

decomposition of an H2O2 solution at 240nm and calculated

as H2O2 reduced per mg of protein per min [38]. GPX activity

was assayed as previously described [39], in which the reaction

mixture contained potassium phosphate buffer (100nM), guaiacol

(15mM, pH 6.5), H2O2 0.05 % (v/v), and 60μL of protein extract.

Guaiacol oxidation was monitored at 470nm and an enzyme unit

was defined as the production of 1μm of oxidized guaiacol per mg

of protein per min. SOD activity was measured by adapting the previously

described chromogenic assay [40] for leaf tissue protein

extract analysis. Briefly, for the reaction 225μL sodium pyrophosphate

(pH 8.3, 0.025M), 18.8μL (186μM) phenazine methosulfate,

56.3μL (300μM) nitroblue tetrazolium, 93.7μL distilled water, and

5μL of protein extract were mixed. To initiate the reaction, 37.5μL

(780μM) nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide was added, incubated

for 1.5 minutes and 187.5μL glacial acetic acid were added to

stop the reaction. The chromogen was extracted by addition of

700μL n-butanol followed by incubation for 10min, centrifugation

at 20,000g for 5min, and absorbance measurement at 560nm. For

GR activity measurement, the reaction was started by the addition

of oxidized glutathione, and the decrease in absorbance at 340nm

every min over a 3min period was read [41]. GR activity corresponded

to the amount of enzyme required to oxidize 1μmol min-1

of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. For all enzyme

activity analyses, results were expressed as U mg-1 protein.

Statistical analysis

For all variables analyzed, each experiment was performed in

triplicate. The data were expressed as average ± standard deviation

(SD) of the three independent replicates as a measure of dispersion.

For the variable NL, FA, PRL, and DLR, the data were evaluated

by an analysis of variance (ANOVA) by ranks (Kruskal Wallis

test) and compared using a nonparametric multiple comparison

test proposed by Conover [42] because the variables evaluated did

not show a normal distribution and had heterogeneous variances.

The adjustment to the premises was verified through the tests of

Shapiro Wilk and Levene. PCA was performed with Pearson correlation

matrices to represent a two-dimensional plane of treatment

effects upon the five morphological traits [43]. The values

of eigenvectors higher than the mean of the minor and the major

values of the component were considered as significant.

Data obtained from biochemical analyzes were processed

using a factorial ANOVA using a fixed effect model, in which the

factors consisted of the treatments (XGO±NaCl) and the days after

each treatment (two and five days). Previously, compliance with

the normality and homogeneity premises were verified through

the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests. All statistical analyses were

performed with the InfoStat program [44].

Resultst

Effect of XGO on germination and growth of Nicotiana

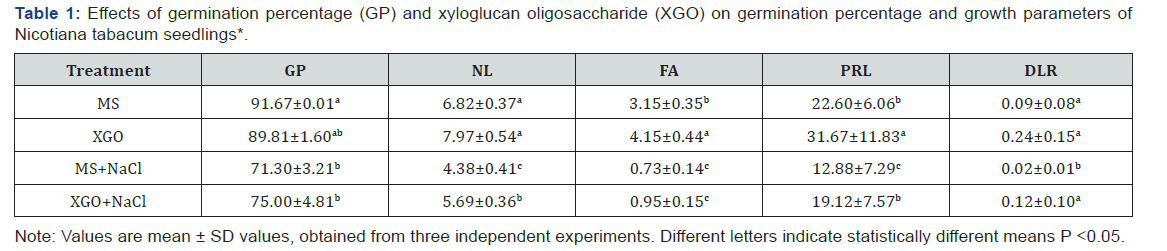

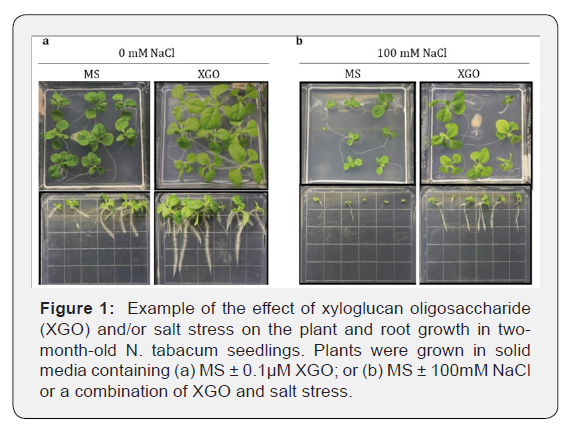

The effects on GP and plant and root growth of N.

tabacum

seedlings, grown with MS ± 0.1μM XGO, salt stress with ± 100mM

NaCl, or a combination of XGO and NaCl are shown in Table 1 and Figure

1. GP was statistically similar between the negative control

and 0.1μM of XGO (close to 90%). However, GP was significantly reduced

to 71% and 75% with 100 mM NaCl and 0.1μMXGO+100mM

NaCl, respectively, compared to the MS negative control (P<0.05).

Both salt stress control (MS+NaCl) and XGO+NaCl were statistically

similar. On the other hand, 0.1μM XGO significantly caused a

promotion in FA and PRL in two-month-old N. tabacum seedlings

compared to negative control, but no statistical differences were

observed in NL or in DLR. Moreover, when XGO was combined

with 100 mM NaCl, there was a significant increase in NL, PRL,

and DLR (P<0.05) related to salt control, but no statistical

differences

were observed in FA (Table 1 & Figure 1). Thus, addition of

100 mM NaCl caused an inhibition of NL and PRL by 36.3% and

43%, respectively, in N. tabacum seedlings compared to the MS

negative control. Nevertheless, the inhibitory effects of salt stress

on NL and PRL were reduced to 16.5% and 15.4%, respectively,

compared to untreated control when XGO was incorporated in the

media.

MS: Negative control; XGO: 0.1μM); MS+NaCl: Salt

stress with 100mM NaCl; XGO+NaCl: 0.1μM XGO + 100mM NaCl; GP:

Germination percentage;

NL: Number of leaves; FA: Foliar area (mm2); PRL: Primary root length

(mm); DLR: Density of lateral root.

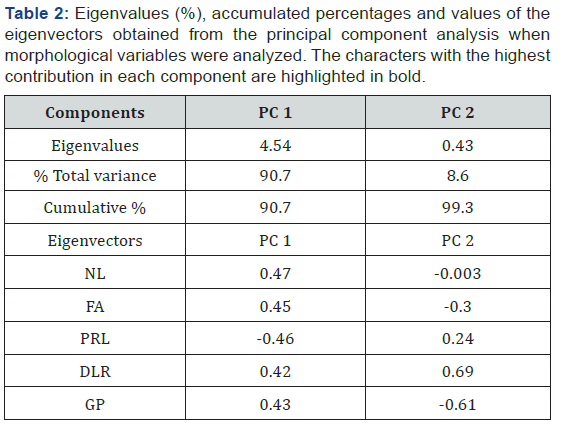

The PCA explained the contribution percentage of each component

to the total variation with the five quantitative characters

evaluated (GP, NL, FA, PRL, and DLR) and each treatment (XGO

and/or salt stress) (Table 2). The first two principal components

(PC 1 and 2) justified 99.3 % of the total variation. The characters

with the greatest contribution to variability consisted of NL, FA,

and PRL in PC 1, and DLR and GP in the PC 2. The biplot chart

of first and second component showed that PRL and DLR were

significantly correlated (P<0.05) in addition to NL, FA, PG, and NL

with PRL (Figure 2). There is a separation between treatments

with NaCl either with or without XGO application in the first principal

component, and in component 2 there was a clear separation

of XGO treatments from those without XGO. The higher values in

PRL, DLR, and NL correspond to treatments where XGO has applied

alone, compared to those where it was combined with salt

stress. In the second component, DLR and GP characters showed

the highest positive and negative contribution, respectively. Also,

there was a well-defined separation of XGO and XGO+NaCl from

MS and MS+NaCl, with the higher average DRL seen with the XGO

values.

Changes in proline and total chlorophyll content

Figure 3 shows the effect of XGO and salt stress on proline

and chlorophyll contents of N. tabacum leaves measured after two

and five days of induction. It can be noticed that treatments without

salt (MS±XGO) exhibited no significant differences in proline

content after two and five days of treatment (Figure 3a). Additionally,

salinity stress in N. tabacum seedlings promoted significant

proline accumulation compared to untreated control at both

time points. However, the results obtained XGO+NaCl application

reflects a gradual and significant increase in the proline content,

which is 75.98% higher than salt stress control after five days of

treatment (Figure 3a).

Total chlorophyll (Chl a+b) content was significantly higher

after XGO application compared to the untreated control, which

reached the highest levels among all treatments at both time

points (Figure 3b). Also, as expected the Chl a+b content was

significantly reduced by salinity stress in N. tabacum leaves compared

to the untreated control and remained constant over time

(P<0.05). On the other hand, XGO combined with NaCl produced

a significantly higher Chl a+b content (29.58% upper) compared

to salt stress control after five days of treatment, which reached

levels similar to the negative control.

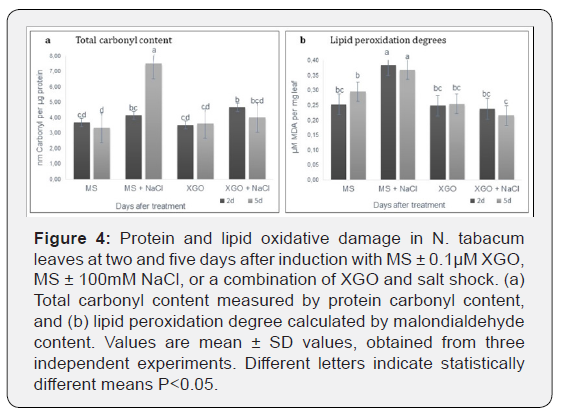

Changes in protein and lipid oxidative damage

The effects of XGO and salt stress on protein oxidation, measured

as total carbonyl contents, in N. tabacum leaves at two and

five days after induction is shown in Figure 4a. Plants treated with

XGO exhibited no significant differences in total carbonyl content

related to control plants after two and five days of treatment. On

the other hand, NaCl application significantly increased its content

by 67.10% compared to the untreated control after five days. In

contrast, at the same time point, XGO application combined with

salt stress significantly reduced protein oxidation in N. tabacum

leaves by 98.45% compared to the salt stress control.

Lipid peroxidation was calculated in terms of MDA content

as an indicator of lipid oxidative deterioration caused by severe

oxidative stress in N. tabacum leaves at two and five days after induction

(Figure 4b). XGO application caused the MDA amounts to

remain constant over time. On the other hand, leaves from plants

exposed to salinity stress demonstrated significantly higher MDA

accumulation compared to untreated control at both time points.

However, XGO application and salt stress also significantly caused

a reduction in lipid peroxidation by 51.88% compared to salt

stress control after five days of treatment.

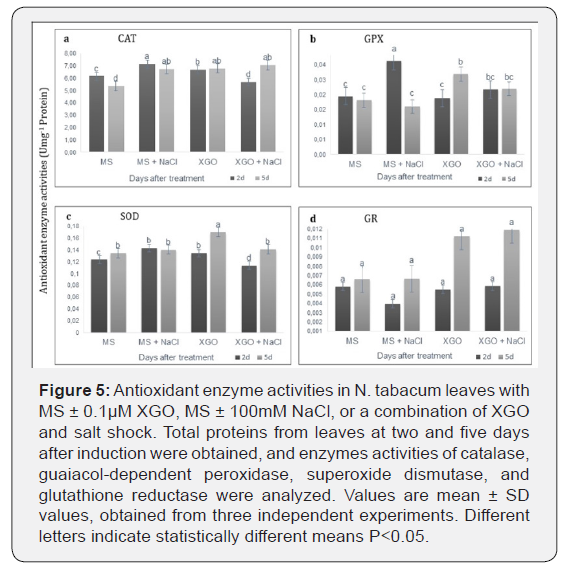

Changes in activities of enzymes from the antioxidant system

We also examined four oxidative stress response

enzyme

markers in the context of their activities. Figure 5 shows the effect

of XGO application and salt stress on the activities of the antioxidant

enzymes, CAT, GPX, SOD, and GR in N. tabacum leaves after

two and five days of induction. The results showed that five days

after treatment with XGO alone resulted in a significantly higher

CAT, GPX, and SOD activities over time compared to the negative

control (P <0.05) (Figure 5a-c). GR activity was not significantly

affected by the application of any treatment (Figure 5d). Salt shock

with 100mM NaCl induced significantly higher CAT, GPX, and SOD

activities two days after induction compared to the negative control.

After five days in the presence of NaCl, GPX decreased, but

CAT activity remained higher (P<0.05) than the untreated control.

There was also an apparent increase in CAT, GPX and SOD activities

after five days of treatment with XGO+NaCl, but their levels

were statistically similar to those of salt control (Figure 5a–c).

Discussion

This study provides evidence concerning the effects of exogenous

application of XGOs on enhancement of N. tabacum growth

and development under saline conditions and salt shock in order

to allow them to overcome the salt-stress limitations. Clearly, under

the conditions used in the current work, XGO alone had a positive

effect on NL, FA, and PRL although it was ineffective in promoting

DRL. However, combined with continuous salt stress, this

effect is rearranged, and XGO causes an increase in NL and PRL in

addition to promoting lateral root formation although no changes

in FA were observed compared to the salt control. Consequently,

in the presence of XGO the plants managed to recover from limitations

imposed by salt, so they display visible morphological characteristic

improvement (Figure 1).

The analysis of eigenvalues corresponding to morphological

changes is based on PCA analysis and explains >99% of the total

experimental variability within the two first components. This is

almost 100 % of the experimental variability that was achieved

by reducing up to two principal components. The five evaluated

traits showed a high contribution in one of the two first principal

components; thus, each trait was very important to explain the

variability observed in the experiment. PC 1, which explains the

highest percent of variability (90.7%) allowed for separation of

treatments under salt stress (100mM of NaCl) from those without

NaCl. The highest values of NL, PRL, and FA were obtained in the

medium with XGO and without salt stress, which were projected

in the positive quadrant of the component. This result clearly indicates

that XGO in the medium enhanced PLR and increased FA and

NL in tobacco seedlings. PC 2, which explains the rest of the variability

(8.6%), separates the treatments with XGO from the treatments

without this biostimulant. In this component, the traits that

showed the highest contribution were PG and DLR. According to

these findings, the presence of XGO in the medium stimulated

DLR, but the highest values of PG were obtained in the MS medium

without NaCl.

These results confirmed that external application of 0.1μM

XGO positively influenced plant growth and morphological features

even under salt stress conditions and could be correlated

with auxin-like activity. It is known that at approximately 1μM, at

least four different cellotetraose-based XGOs (XXXG, XXLG, XXFG,

and XLLG) mimic auxin by inducing growth [45]. In a previous

study, we confirmed that auxin-like activity of the same XGO fraction

mix and concentration used in this work on Arabidopsis thaliana

seedlings [18]. These are important findings since the ability

of a biostimulant to influence plant hormonal activity is one of

their many important benefits because they can exert large influences

that eventually will improve their health and growth. As

plant growth regulators plays an important role as chemical messengers,

they alert the plants when stressful environmental conditions

exist so they can initiate or increase their stress response

processes [46].

In this context, XGO may be acting as a “switches” that turn on

the plants for stressful situations by altering hormonal balances.

Zhang and Schmidt (1999) discuss the “switch” concept and give

some examples of other types of biostimulants that reinforce our

evidence. In this context, the results also suggested that exogenous

XGO applications could be acting as “pre-stress conditioners”

[46] and their effects are manifested by improving osmotic regulation,

photosynthetic efficiency, or by causing an increase in antioxidant

levels. This argument is based on the results in which it was

shown that 21-day-old plants exposed to external application of

0.1μM XGO had higher proline accumulation and total Chl content

in addition to higher CAT activity levels, GPX, and SOD compared

to untreated plants. Of more interest was their effect when applied

in combination with salt shock (XGO+NaCl) compared with those

treated with NaCl alone (MS+NaCl). In this case, the highest recorded

proline levels in addition to higher total Chl were observed

after five days of treatments. Enhancement of this antioxidant machinery

could be reflected in significant protein oxidation (total

carbonyl content) and lipid peroxidation reduction. Therefore, it

can be seen that the XGOs help the plant to cope with the effect of

saline stress via proline accumulation.

Osmotic regulation is an important mechanism for plant cellular

homeostasis under saline conditions in which proline is the

most common osmolyte for osmoprotection [47]. The higher accumulations of proline recorded with XGO and NaCl at five days after

treatment could be correlated with stress tolerance and may participate

in the stress signal influence on adaptive responses (Figure

2) [6]. Proline also contributes to stabilization of sub-cellular

structures (such as membranes and proteins), and its cytoplasmic

accumulation could help reduce oxidative stress-generated plant

protein and membrane damage after exposure to salinity [6]. This

effect can be inferred because of lower total carbonyl content levels

since protein-bound carbonyls represent a marker of global

protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation products as biomarkers

for oxidative stress that were observed in plants treated with

XGO+NaCl (Figure 3). Therefore, XGO indirectly helps the cell cope

with salt stress by maintaining cellular osmotic adjustment and

protein and lipid integrity.

Another important result indicated that XGO seems to mitigate

negative effects on photosynthesis in stressed plants by increasing

Chl content. This parameter was used because of salinity-

induced increase in chlorophyllase activity with the consequent

degradation of chlorophyll (at least transiently). Consequently, we

can deduce that the increase in exogenously XGO-induced total Chl

content enabled tobacco plants to tolerate salt-stress in addition

to promoting their development and growth. Similar results with

photosynthetic pigments were obtained in our lab when the same

XGO fraction mix was evaluated on A. thaliana seedling growth under

saline stress [48].

Regarding the activity of antioxidative enzymes, exogenous

application of 0.1μM XGO increased CAT, GPX and SOD enzyme

activities compared to the negative control after five days of treatment.

Due to the fact that no significant XGO+NaCl effects on enzymes’

activity that were analyzed in this work were observed, it

would be advisable to analyze other antioxidant enzymes to expand

the analysis in addition to determining its mode of action in

the enzymatic antioxidant system.

Our study revealed that XGO seem to be working as metabolic

inducers that trigger the physiological responses mentioned

above. Some results support that xyloglucan fragments do not

penetrate the cell, but instead, it has been suggested that the existence

of specific receptors on the plasma membrane, which interact

with the fragments, activate a signaling cascade inside the cell

[49]. However, to date, no specific candidate has been identified as

a possible receptor of these molecules [19]. Also, it has been suggested

that they can promote modifications or integrate into the

cell wall, which can affect not only the extracellular events in the

wall but also intracellular events [50]. These authors demonstrated

that incubation of pea stem segments partially bisected longitudinally

with a xyloglucan oligosaccharide (9mM XXXG), accelerated

the cell elongation by integration of xyloglucans as they were

incorporated into the cell wall and became transglycosylated by

xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET). According to this, XGO’s

effects observed in our work may also result from a signal transduction

XET-mediated or -induced cell wall modification cascade

but not from the oligosaccarides’ direct actions.

Conclusion

Overall, we conclude that XGO can exert beneficial impacts on

tobacco plants’ stress response either through hormone-like effects,

osmotic regulation, photosynthetic efficiency improvement,

and increase in antioxidant levels. They promote the proline accumulation

as an organic osmolyte and increase total chlorophyll

content and modify some antioxidative enzymes’ activities that

eventually affect development of plant roots’ growth and development

under salt stress. Further in vivo studies are needed to

confirm the antioxidant effect of XGOs during salt stress in crop

plants as well as to unravel their mechanism of action on oxidative

responses. However, according to these results, the exogenous application

of XGO as biostimulant at very low concentrations could

be considered an alternative for improving the growth and productivity

of crops of agronomic importance under salt stress.

To know more about Journal of Agriculture Research- https://juniperpublishers.com/artoaj/index.php

To know more about open access journal publishers click on Juniper publishers

Comments

Post a Comment