Biomass Yield and Nutritional Quality of Different Oat Varieties (Avena sativa) Grown Under Irrigation Condition in Sodo Zuriya District, Wolaita Zone, Ethiopia-Juniper Publishers

Journal of Agriculture Research- Juniper Publishers

The objective of this study was to evaluate the

performance of five forage oat varieties (CI- 8237, Lampton, CI- 8235,

CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2291 and CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2806) under irrigation condition

in Wolaita Zone, Sodo Zuriya Worda, at Kokate Farmers association,

during off season in the year 2017. The experiment was laid out in a

randomized complete block design with three replications. Data were

collected at 50% flowering stage. The major data recorded were date of

emergence, plant height, number of leaves per tiller, number of leaves

per plant, number of tillers per plant, fodder yield and chemical

composition at 50% flowering stage respectively and grain and straw

yield at maturity stage. The varieties differed in yield and yield

related parameters. The varieties showed variations in terms of number

of leaves per tiller, number of tillers per plant, number of leaves per

plant, fodder and dry matter yield at 50% flowering stage and straw

yield. Variety CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2291 produced lower (p < 0.05) number

of leaves per plant, number of leaves per tiller and plant height than

the rest of the varieties. However, CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2291 produced

significantly higher (p < 0.05) amount of green forage (42.4t ha-1)

and dry matter (12.2t ha-1) yield at 50% flowering stage. All tested oat

varieties had similar grain and straw yield. CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2806 had

lower NDF (41.6%), ADF (22.1%) and ADL (1.98g per kg) concentrations and

the highest CP (15.3%) and IVDMD (73.9%) content. Therefore, it is

concluded that, CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2806 and CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2291 were

recommended to use in the upper parts of midland and highland areas due

to reasonably higher nutritional (CP) value and better forage yield,

respectively.

Keywords: Biomass yield; Chemical composition; Lampton; Yield parameters

Abbreviations:

DM: Dry Matter; CP: Crude Protein; EE: Ether Extract; ADL: Acid

Detergent Lignin; ADF: Acid Detergent Fiber; NDF: Neutral Detergent

Fiber; IVDMD: In Vitro Dry Matter Digestibility

Introduction

In Ethiopia, the livestock sub-sector has significant

contribution to the national income [1] and for the livelihoods of

rural and urban communities. However, productivity of animals remained

at low level due to feed shortage and nutritionally unbalanced supply of

feeds [2]. A large proportion of livestock feed resources in Ethiopia

comes from natural pastures, crop residues and aftermath grazing [3,4],

but such feed resources cannot promote increased animal productivity due

to their nutritional limitations (such as low crude protein, mineral,

vitamins and higher fiber content), lower intake and digestibility [5].

The major problems with livestock feeding occur in developing countries

like Ethiopia, particularly during the long dry season, when there is

insufficient

plant biomass carried over from the wet season to support domestic

livestock species [6].

According to Mulualem and Molla [7] when improved

forages are integrated and developed at household level in a sustainable

manner, animal productivity would be increased. Currently, there has

been a rapid governmental dedication which has been implemented through

changing livestock improvement strategies to bring a paradigm shift in

livestock industry. The strategy promotes enhancing livestock

productivity through improving availability and quality of feed

resources [1].

Different strategies can be employed to boost feed

availability and improve nutritional deficiencies of local feed

resources. One of such strategies that receiving attention and has been

considered as best options is use of improved forage species for animal

feeding [1]. However, the adoption rate of improved forages introduced

to farmers level in Ethiopia is usually low and unsatisfactory

due to forage seed and land shortage in crop-livestock

mixed agriculture [8], reluctance of some smallholder farmers in

forage production [1], technical problems such as managing the

seedlings, insect damage and poor extension services. Information

is also limited on agronomic practices, biomass production, and

nutritive value of various improved forage varieties, including oat

crop at the farmer’s level. CSA [9] report indicated that the

contribution

of improved forage to livestock feed source is about 0.22%.

Effort in extension and research work and strengthening producers’

capacity through continuous training on cultivated fodder

crops and improved grass species such as oats are not common

and well adopted even in highland areas where feed shortage is a

crucial problem [8].

Oats (Avena sativa L.) is one of the well-adapted and important

fodder crops grown in the highlands of Ethiopia, mainly under

rain fed conditions. It is also one of the important fodder crops

widely grown during the winter season when livestock face green

fodder shortage and majority of the feed start declining and finally

drying [10]. It is also ranked as sixth in world’s cereal production

following wheat, maize, rice, barley and sorghum. However, it has

been tested under irrigation conditions because rainfall is not reliable

most of the years.

Improved varieties of oat can produce a three-fold green fodder

60 to 80t ha-1. This amount can feed double number of animals

per unit area compared with the traditional fodder production

practices [11]. Straw of oat is soft and its grains are also valuable

feeds for dairy cows, horses, young breeding animals and poultry.

It can be fed in many forms like green forage or silage to animals.

Oat grains have high content of proteins, which is relatively better

in quality, compared to other cereals. The contents of Mg, Fe, P, Ca,

and vitamins E and B1 are also higher in oats compared with other

cereals [12].

Wolaita Zone in general and Sodo Zuriya specifically is known

with high human population and small and fragmented land size,

thus there is high feed shortage, which has resulted in decreased

livestock production and productivity. Cultivation of improved forages

like oats is important mainly in highlands and in areas where

market-oriented livestock production is practiced supporting the

livestock sector through improved production of high amount of

feed from small area of land. Furthermore, there is no adequate information

on comparative productivity and performance of different

oat varieties under Wolaita situation. Therefore, the objective

of this study was to evaluate Agronomic performances, yield and

Nutritional Quality (chemical composition) of five oat varieties

under irrigation condition in the highlands of Sodo Zuriya Woreda,

Wolaita Zone, Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

Description of study area

The experiment was conducted in Wolaita Zone, Kokate Farmers

administrations, Ethiopia. The site is situated at a latitude and

longitude of 39º 36’ S and 61º 64’ W, respectively, with an altitude

of 1916m.a.s.l. The agro-ecology of the district is 5% Dega and

95% Woyna Dega. The mean annual temperature ranges between

18 ºC - 28 ºC. The annual rainfall ranges between 1200-1300mm.

Rainfall occurs in two distinct rainy seasons, ‘Kiremt’ (heavy rainy

season) occurs in summer (June, July and August) and ‘Belg’ rain

(light rainy season) occurs in spring (from mid - January to mid

- May). The major soil type of the area is sandy - loam with pH value

of 6.70. The organic matter percentage (1.52%), total nitrogen

content (0.22%) and available phosphorus content (6.33) ppm

were also reported.

Treatments and experimental design

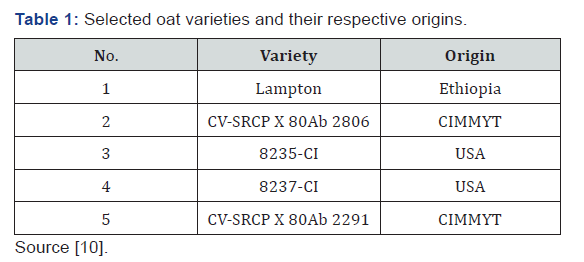

The experiment consisted of five treatments of oat varieties

namely Lampton, CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2806 (called Acc 2806), 8235-

CI, 8237-CI and CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2291 (called Acc 2291) (Table 1).

The varieties were selected due to the adaptability and availability

of seeds in the area. The experiments were laid out in randomized

complete block design (RCBD) with three replications on well

prepared seedbed. The plot size was 2m x 3m. The blocks were

separated by a space of 1m and plots were spaced 0.50m apart.

Each plot had 10 rows spaced 20cm apart and data were collected

by 0.25m2 quadrant. The seed rate used was 100kg ha-1 and drill

method of sowing was used. NPS fertilizer was applied at sowing

time at a rate of 100kg ha-1, respectively [13,14].

Land preparation, management and irrigation practice

The varieties were sown on 28th of December 2016 at the beginning

of the light rainy season. Land was ploughed three times

before the start of the field experiment. The seed was obtained

from Agricultural Research Center and checked for weed seeds

and other dead irregular shapes to increase the germination

percentage. Then the plots were uniformly fertilized with NPS at

a rate of 100kg ha-1 (60g of NPS per plot) at the time of sowing

[15,16]. Weeding was conducted three times from sowing up to

maturity stage. The experimental plots were uniformly irrigated

starting from sowing date up to maturity. Two times a day; morning

at 12:00 - 1:30hrs and afternoon 11:00 - 12:30hrs were applied

up to emergence. After emergence, application of water decreased

and applied every two days.

Antifungal resistance

Physiological and agronomic data

a. Growth: The developmental process such as days to emergence,

days to 50% flowering and maturity stage were recorded.

b. Plant height (cm): The average plant height was measured

from ground to the tip of the main stem. The measurement

was done by taking ten random plants at 50% flowering stage

from each plot [17].

c. Number: Counts of plant number, number of leaves per tiller,

number of tillers per plant and number of leaves per plant

were recorded at 50% flowering stage. Ten plants from each

plot in a quadrant (0.25m2) were taken to measure number

of tillers per plant, number of leaves per plant and number

of leaves per tiller. Average results from each measurement

were recorded to evaluate the performance [18].

d. Biomass yield: The vegetation from each plot was sampled

using a quadrant of 0.25m2 (0.5m x 0.5m) sizes during a

predetermined sampling period (50% flowering stage). The

quadrant was randomly thrown on a plot and the average

weight of ten plants from the quadrant was used to determine

the biomass yield. The average weight of the fresh fodder was

used and extrapolated into dry matter yield per hectare (t

ha-1). Three adjacent rows from the center of each plot were

taken at 50% flowering stage for fodder yield evaluation [19].

The fresh harvested biomass was chopped into small pieces

using sickle and a sub-sample of 400 g was taken and partially

dried in an oven at 60 ˚C for 48hrs for further dry matter

analysis [18].

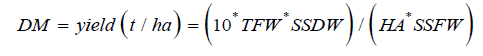

Where:

10 = Constant for conversion of yields in kg/m2 to t/ha

TFW = Total fresh weight from harvesting area (kg)

SSDW = Sub-sample dry weight (g)

HA = Harvest area (m2)

SSFW = Sub-sample fresh weight (g)

e. Grain and straw yield: Grain and straw yield were determined

at full maturity (100% seed maturity) stage. Plants in a

quadrant (0.25m2) size were taken as a whole tied, dried and

straws and grains collected separately. Then grain and straw

obtained from each quadrant were measured and converted

to tones per hectare [20].

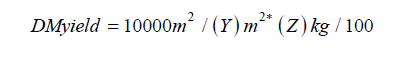

Where:

Z = Yield obtained from sampling area (kg/m2)

Y= Area of sampling site in m2

Chemical composition and in vitro dry matter digestibility:

The collected and partially dried oat varieties green forage

(50% flowering stage) was transported to Hawassa College of Agriculture

Animal Nutrition Laboratory for chemical analysis. The

samples were dried to a constant dry weight in an oven at 100 ± 5

˚C overnight to determine percent dry weight before any analytical

procedures [21]. Then the dried samples were ground to 1mm

mesh size using Willy mill, packed into paper bags and stored

pending to further laboratory works. Chemical composition (Dry

matter (DM), Crude protein (CP), Ash, Ether Extract (EE), Acid detergent

lignin (ADL), Acid detergent fiber (ADF), neutral detergent

fiber (NDF) and in vitro dry matter digestibility (IVDMD)) of the

forage samples were analyzed. Nitrogen content was determined

using Kjeldhal method [21] and then CP content was calculated

as N x 5.7 for grain yield. The ash content of the samples was determined

by complete burning in a muffle furnace at 550 ˚C for 3

hours [21]. The NDF, ADF and ADL were determined according to

procedures of Van Soest and Robertson [22].

IVDMD of oat was estimated using a Daisy II Incubator on a

dry matter basis. Sample of 0.5g from each replication were taken

and dried at 39 ˚C for 48 hours. The dried and ground samples of

oat were placed in ANKOM tubes filter bags (F57) made from polyester/

polyethylene/extruded filaments. Weigh each F57 filter bag

and record weight (W1). Zero the balance and weigh sample (W2)

directly into filter bag. Heat seal bag closed and place in the Daisy

II Incubator digestion jar (ANKOM Technology Method 3, ANKOM

Technology -08/05).

Statistical analysis

Generated data were analyzed using the General Linear Model

procedure of statistical analysis system [23]. Means were separated

using Least Significant Difference (LSD) at 5% significance

level.

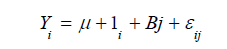

Where Yi = The response variable (i. is agronomic parameters,

yield and chemical composition)

μ = Overall mean

li = The ith effect of variety (i= 1, 2, 3,4,5)

li = The ith effect of variety (i= 1, 2, 3,4,5)

εij= Random error

Results and Discussion

Physiological and agronomic data

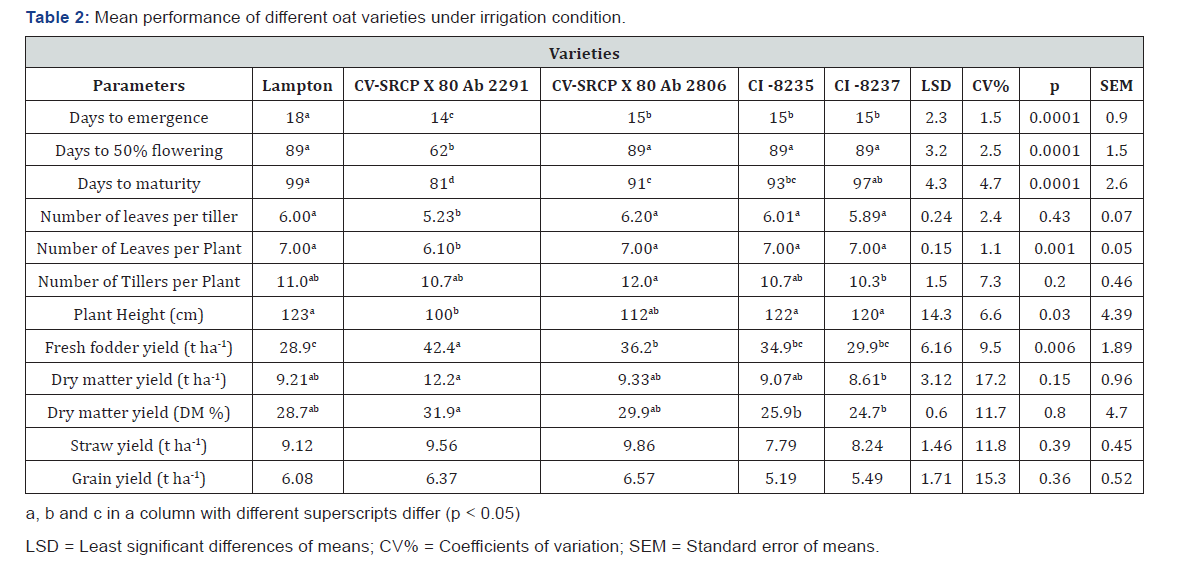

Days to emergence, 50% flowering and maturity stages:

The

emergence date was relatively similar for all treatments and it

took around 14- 21 days in all plots. Relatively prolonged days to

emergence in this study was most likely due to sowing season, high

temperature and lack of enough moisture. Average emergences of

the varieties were 60% at first week and above 95% at second

week. Only one variety (CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2291) (p < 0.05) reached

50% flowering stage at 62 days than the rest varsities (89 days

after sawing). CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2291 variety reached to full maturity

early (81 days) as compared to other oat varieties (91 - 99

days) (Table 2). The grain filling period in the present experiment

ranged from 81 to 99 days however, the same varieties in previous

study [16] reached between 64-80 days, which was shorter than

current studied varieties due to differences in sowing season and lack

of moisture content in the area. Hellewell et al. [24], attested

that the major difference in maturity among oat cultivars related

to differences in the length of the vegetative growth stage, not the

grain filling period and thus the fast growth of early maturing

cultivars

is explained in terms of a shortened vegetative growth stage

rather than a shortened grain filling period. Late maturing varieties

tended to have comparatively shorter grain filling period than

early maturing varieties as reported by Feyissa [16].

Number of leaves per tiller: Number of leaves per tiller at

50% flowering stage is shown in Table 2. Variety CV-SRCP X 80Ab

2291 had statistically lower number of leaves per tiller (p < 0.05)

than CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2806, CI-8237, CI-8235 and Lampton at

50% flowering stage. This might be due to the early maturity of

CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2291 as compared to the rest varieties, the earlier

to reach maturity the lower the number of leaves per plant as well.

According to Gebremedhn et al. [17], the number of leaves per tiller

varied from 6.89 to 4.89 at 50% flowering stage where as in

current study it varied from 6-5 which were agreed. Oat varieties,

Sargodha-2011 and PD2LV65 produced 6.62 and 5.37 number of

leaves [20] per tiller at 50% flowering stage respectively which

were comparable with the current findings.

Number of leaves per plant: The number of leaves play vital

role in growth and development of plant. The increase or decrease

in number of leaves per plant has a direct effect on the yield

of forage crops. Significant (p < 0.05) variation in the number of

leaves per plant was observed at 50% flowering stage (Table 2).

The number of leaves per plant at 50% flowering stage were higher

for the varieties CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2806, Lampton, CI-8235 and

CI-8237, and statistically lower number was recorded for the variety

SRCP X 80Ab 2291 (6.10). Varieties that produced maximum

number of leaves per plant differed by 15% from the variety (CVSRCP

X 80 Ab 2291) that produced minimum number of leaves

per plant. According to Khan et al. [18], the oat varieties; SGD-40,

SGD-2011 and SGD-37 produced 7.50, 7.13 and 6.99 numbers of

leaves per plant at 50% flowering stage, respectively, which were

comparable with the current findings.

Number of tillers per plant: At 50% flowering stage CV-SRCP

X 80Ab 2806 produced the highest number of tillers per plant

(12.0) followed by Lampton (11.0), CI-8235 (10.7) and CV-SRCP

X 80Ab 2291 (10.7) and the lowest was recorded for the variety

CI-8237 (10.3) (Table 2). CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2806 variety produced

16.5% more tillers per plant than variety CI-8237 that produced

minimum (10.3) number of tiller per plant. In previous study [17],

Lampton showed highest number of tillers per plant (14.2) followed

by 8237-CI (13.30 tillers per plant) at 50% flowering stage

which were higher than the current observations. These results

are in line with the finding [17,25] who reported that variation in

environmental conditions and genetic makeup cause the variation

in plant height and number of tiller per plant. However, currently

studied varieties showed better performance than 80-SA-130 variety

which produced 9.25 tillers per plant at 50% flowering stage

[17]. Varieties F-411 and DN-8 were found to have similar tillering

capacity (12 and 11 tillers per plant) respectively [26], which are

agreed with the current observations. However, varieties, SGD-3,

SGD-50, F-408 and F-301 produced 6.67, 6.33, 7.00 and 7.03 number

of tiller per plant at 50% flowering stage, respectively, which

were lower than the current varieties [18].

Plant height (cm): Plant height is one of the yield components

contributes to green fodder and dry matter yield [27]. Plant

height at 50% flowering stage are shown in Table 2. CV-SRCP X

80Ab 2291 had significantly (p < 0.05) shorter height than the

rest varieties at 50% flowering stage. Lampton produced maximum

height (123cm) at 50% flowering stage. In previous studies

[17], Lampton produced the maximum height (178cm) followed by 8237-CI (170cm). The shorter height in the current observation

might be due to difference in environmental condition and

the sowing season [28]. However, varieties PD2LV65 (124cm),

No.725 (118cm) [29] and SGD-46 (119cm) [18] produced similar

result with the present observations at 50% flowering stage. Other

varieties such as UPO 2005-1 (135cm), JO 2003 -78 (126cm),

OS -6 (126cm), Kent (125cm), JHO-822 (123cm) and SGD Oat-

2011(130cm) showed more or less similar results with the current

observations [26,30].

Green forage and dry matter yield

The green forage yield is one of the most important traits and

the ultimate goal of forage production is to obtain a high biomass

with a reasonable quality. The green forage yield (t ha-1) of the varieties

were statistically significant (p < 0.05) to each other at 50%

flowering stage (Table 2). Variety CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2291 produced

the highest (p < 0.05) green forage yield (42.7t ha-1) followed by

CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2806 (36.2t ha-1) and the lowest was recorded for

Lampton (28.9t ha-1). Variety that produced higher green forage

yield (CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2291) was 31.8% higher than lower green

forage yield (Lampton) variety. The highest green forage yield of

variety CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2291 might be due to the thick size of the

steam than the other tested oat varieties. In previous studies the

maximum (47.6t ha-1) and minimum green forage yield 33.3t ha-1

were obtained from the oat varieties No.725 and CK1, respectively

[29] which were in agreement with the current finding. Relatively

higher amount (67.2t ha-1) of Lampton green forage yield

than the current observation was reported by Gebremedhn et al.

[17] at 50% flowering stage. Similarly, Saleem et al. [20] recorded

maximum green forage yield from Sargodha-2011 (72.7t ha-1) and

lowest green fodder yield from Varity PD2LV65 (62.4t ha-1). The

lowest fodder yield observed as compared to previous findings

might be due to environmental influence such as sowing month

variation and high temperature during practical field work in the

area. But, current study was in agreement with Muhammad et al.

[31] which produced PD2LV65 (41.0t ha-1) and F-411 (45.9t ha-1)

green forage yields.

Similarly, the maximum dry matter yield was produced by the

variety CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2291 (12.2t ha-1) (P < 0.05) than CI-8237

(8.61t ha-1) at 50% flowering stage (Table 2). According to Khan

et al. [18], the dry matter yield of SGD-3 (9.73t ha-1) were agreed

with current CI-8237, CI-8235, Lampton and CV-SRCP X 80Ab

2806 varieties. Varieties Avoni, Ravi, CK-1, F-311 and F-411 also

produced 10.5, 10.1, 10.9, 11.1 and 9.1t ha-1 [31] which were similar

with the present observations.

Grain and straw yield

Grain and straw yield of oat varieties were presented in Table

2. The grain and straw yield among oat varieties were not statistically

different (P > 0.05). However, numerically the highest grain

and straw yield was recorded for the variety CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2806

(6.57t ha-1 and 9.86t ha-1), respectively which relatively produce

26.6% and 17.5% more grain and straw yield than the lowest

grain and straw producing variety CI-8235 (5.19t ha-1 grain and

7.79t ha-1 straw). According to Feyissa et al. [16], Coker SR res 80

SA 130 gave exceptionally higher grain yield (10.6t ha-1) than CVSRCP

X 80 Ab 2291 (8.64t ha-1) and CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2806 (8.60t

ha-1) varieties which were higher than the current observation.

The variation might be due to sowing season, where the current

experiment was conducted on the dry season in irrigation bases

while the previous once was in the main rainy season. The varieties

Lampton, CI-8235 and CI-8237 that were produced 6.52, 6.68

and 6.84t ha-1 grain yield in previous studies [16] was in agreement

with the current study. Whereas, according to Siloriya et al.

[30] varieties NDO-1 and Kent produced 3.64t ha-1 and 3.52t ha-1,

respectively, which were lower than the current grain yield.

According to Feyissa et al. [16], relatively higher straw yield

than the current finding were observed by CI-8235, CV- SRCP X 80

Ab 2806, CI-8237, Lampton and CV- SRCP X 80 Ab 2291 varieties

which were 14.1t ha-1, 14.1t ha-1, 12.7t ha-1, 12.7t ha-1 and 13.1t

ha-1 respectively. Variety OS-6 (10.6t ha-1) followed by JO 2003 -78

(10.2t ha-1) also produced higher straw yields [30]. The variations

in grain and straw yield might be due to differences in planting

seasons, plant height and number of tillers per plant. Whereas,

varieties 79 Ab 382 (TX) (80 SA 94), SRCP X 80 Ab 2764 and PI-

338517 produced 9.95t ha-1, 9.90t ha-1 and 9.86t ha-1 straw yield

[16] were in agreement with current observations. According to

Nazakat et al. [32], varieties PD2LV65, Swan, Tibour and Scott

produced 2.44, 2.40, 1.11 and 0.81t ha-1 grain yields respectively,

which were lower than the current finding.

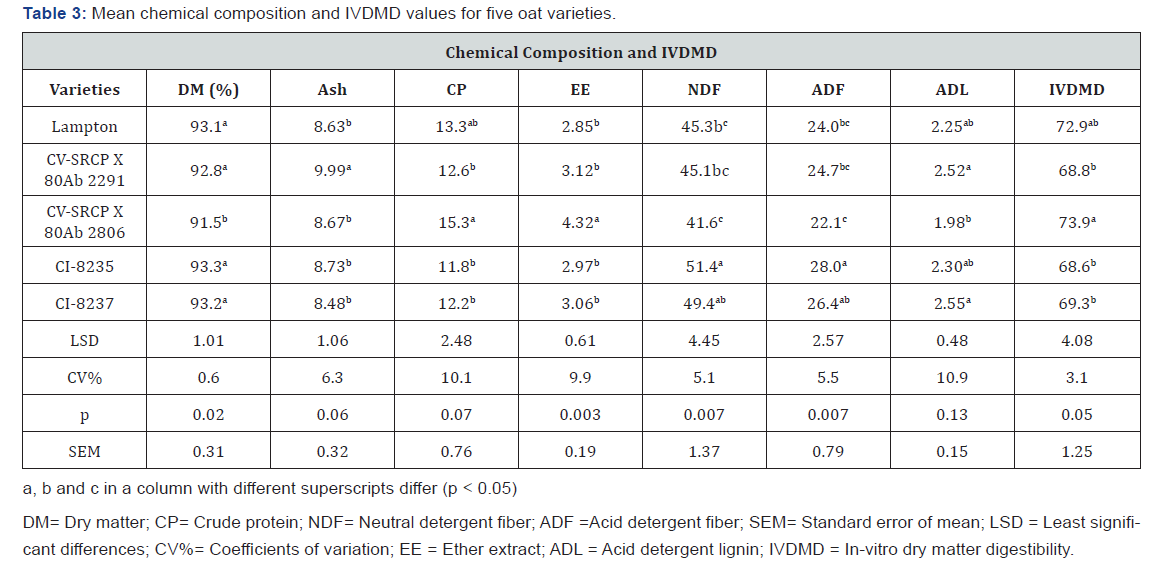

Chemical Composition and in vitro dry matter digestibility

Table 3 indicates chemical composition of five oat varieties.

The highest mean (P < 0.05) DM percentage were obtained in CI-

8235 (93.3%), CI-8237 (93.2%), Lampton (93.1%) and CV-SRCP

X 80Ab 2291 (92.8%) and the lowest was recorded for CV-SRCP X

80 Ab 2806 (91.5%). Variety CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2291 possessed the

highest ash contents (p < 0.05) as compared to the rest tested varieties.

Variation in concentration of minerals might be affected by

factors like varieties Gezahegn et al. [33], growth stage, morphological

fractions, climatic conditions, soil characteristics, seasonal

conditions McDonald et al. [34] and fertilization regime.

Crude protein (CP) content is one of the very important criteria

in forage quality evaluation Khan et al. [18]. The mean CP content

ranged from 11.78% to 15.3% (Table 3). Variety CV-SRCP X 80

Ab 2806 showed better CP (15.3%) content followed by Lampton

(13.3%) than CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2291, CI-8237 and CI-8237 varieties.

According to Saleem et al. [20] maximum CP was recorded in

variety Sargodha-2011 (10.38%) followed by Avon (9.09%) which

were lower than CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2806 in the current study. Relatively

lower CP content was also reported in previous studies for

the varieties Scott (9.86%), Avon (7.80%) and Ravi (6.7%), Muhammad

et al. [31].

Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) content varied between

41.6

and 51.4% (Table 3). The result showed that the NDF content

were significantly affected by varietal difference. The highest and

lowest NDF contents were recorded for CV-8235 (51.4%) and CVSRCP

X 80 Ab 2806 (41.6%), respectively. Geleti [35] indicated

that the NDF contents above the critical value of 60% results in

decreased

voluntary feed intake, feed conversion efficiency and longer

rumination time. According to Van soest Robertson [22] the

critical level of NDF which limits intake was reported to be 55%.

However, the NDF content of all the treatments were observed to

be below this threshold level which indicates no effect on digestibility

and intake.

Acid detergent lignin (ADL) content ranged from 1.98 to 2.55g

per kg DM. The mean ADL content of CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2806 was

significantly (P < 0.05) lower (1.98g per kg DM) than CI-8237

(2.55g per kg DM) and CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2291 (2.52g per kg DM)

varieties. The higher the ADL content, the lower will be the digestibility

of the feed.

Acid detergent fiber (ADF) is the percentage of indigestible

and slowly digestible material in a feed or forage [34]. This fraction

includes cellulose, lignin and pectin. Acid detergent fiber

has a positive relationship with the ages of the plant [36]. In the

present study ADF content of CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2806 was lower

(22.1%) and the highest was observed in CI-8235 (28.0%) and CI-

8237 (26.39%) varieties. The lower ADF content indicates that it

is more digestible and more desirable, which agrees with previous

report of Negash et al. [37] that observed 23.7% of CV-SRCP X 80

Ab 2806 variety. Digestibility decreased as age advanced and this

could be linked to the increased fiber concentration in plant tissue

and increased lignifications during plant development [38]. Kellems

and Church [39] characterized roughages with less than 40%

ADF as high quality and above 40% as low quality. Hence, current

varieties were comparatively lower value of ADF values, this could

be indicative of its better digestibility.

The in vitro dry matter digestibility values (IVDMD) had greater

than 65% indicated good nutritive value, and values below this

level result in reduced intake due to lowered digestibility [40].

Hence, the IVDMD values of studied oat varieties were higher than

65% value. Variety CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2806 (73.85%) produced

maximum IVTDMD and CI-8235 (68.55%) relatively minimum

IVDMD yield.

Conclusion and Recommendation

High human population and the associated land shortage and

feed scarcity both in quality and quantity is one of the challenges

for livestock production in Wolaita Zone. Cultivation of improved

forages with high biomass yield with reasonable quality that can

reach to maturity within a short period of time is essential. The

findings of the present study indicated that the studied varieties

had significantly different (p<0.05) number of leaves per plant,

number of leaves per tiller, number of tiller per plant, green and

dry matter yield at 50% flowering stage. CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2291

variety had yield variations in number of leaves per tiller and

number of leaves per plant from the rest varieties at 50% flowering

stage. Grain and straw yield of all varieties had similar results;

however, variety CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2806 produced 26.6 % and

17.5% more grain and straw yield than CI-8235 variety.

Planting of CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2806 variety followed by

CV-SRCP

X 80 Ab 2291 produced higher grain and straw yield than other

varieties. Higher CP, IVDMD, lower fiber and ADL contents were

also recorded for the variety CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2806. On the other

hand, variety CV-SRCP X 80 Ab 2291 was early emerging, reach

early to 50% flowering stage, early maturing ability and also

significantly

higher fresh biomass yield than the rest varieties. This

Early maturing ability and higher fresh biomass yield at short

period of time increase livestock production and productivity by proving

enough amount of feed for livestock. Therefore, it is recommended

that farmers in high land areas of Sodo Zuriya Woreda

and other areas having similar agro-ecology and soil type could

use CV-SRCP X 80Ab 2806 for higher crude protein, IVDMD, EE and

for lower ADL, NDF and ADL contents. However, CV-SRCP X 80Ab

2291 variety was better for early maturity, fresh forage and dry

matter yield (t ha-1).

To know more about Journal of Agriculture Research- https://juniperpublishers.com/artoaj/index.php

To know more about open access journal publishers click on Juniper publishers

Comments

Post a Comment