Assessment of Growth, Lipid Peroxidation and Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging Capacity of Ten Elite Cassava Cultivars Subjected to Heat Stress-Juniper Publishers

Journal of Agriculture Research- Juniper Publishers

Cassava is an important source of energy-giving food

in the developing countries [1]. Cassava productivity is stable and

reliable, making the crop a candidate for reducing food insecurity,

hunger and poverty in developing countries [2]. Under normal growth

conditions, the crop gives high tuber yield and when the growth

conditions are sub-optimal, cassava tuber yield is satisfactory [1]. For

these reasons, cassava production in developing countries is expanding,

a situation that makes the crop suitable for meeting Sustainable

Development Goals (SDG) [2]. However, empirical evidence from climate

change studies suggested that most cassava production areas would

experience global warming and temperature extremes [3]. Indeed, heat

wave (high temperatures) has been reported during growing period of

cassava in Africa, Asia and Latin America [3]. As a warm temperate crop,

cassava has best

shoot and root growth and development at 25-32 ˚C [2]. Tempera

tures above the normal optimum are sensed as heat stress. Heat stress

upsets cellular equilibrium and lead to severe retardation of growth and

development, and even result in plant death [4]. One of the

physiological damages of oxidative stress caused by heat stress is lipid

peroxidation. Peroxidation results in the breakdown of lipids and

membrane functions by causing loss of fluidity, lipid cross-linking, and

inactivation of membrane enzymes [5]. The extent of lipid peroxidation

can be evaluated by measuring thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

(TBARS) content, which is a secondary breakdown product of lipid

peroxidation [6]. Hydrogen peroxide is the product of the first

detoxification process of superoxide radical by SOD before scavenging by

CAT and other peroxidases. Hydrogen peroxide production invariably

measures ROS scavenging ability of plants under heat stress.

Environmental stresses such as heat stress induce the accumulation of

proline in many plant species [4]. Proline plays a role in cellular

osmoregulation

and also exhibits many protective effects; plants with elevated

proline levels were reported to exhibit enhanced tolerance

to abiotic stresses [7]. Levels of proline can be increased either

by stimulation of its biosynthesis by 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate

synthetase(s) (P5CS) or by inhibition of its degradation by proline

dehydrogenases [7].

Heat stress triggered an upsurge in production of reactive oxygen

species (ROS) such as superoxide radical (O2

−), singlet oxygen

(1O2), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radicals (OH•) [8].

The ROS are produced from different sources in plants. Heat stress

causes ROS production in chloroplasts and mitochondria by disturbing

membrane stability and biochemical reactions such as the

activity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase [9].

In addition, ROS are produced in mitochondria from membrane

instability, resulting in photorespiration and enzymes involved in

cellular respiration such as complex I and III in the mitochondrial

electron transport chain [10]. Furthermore, ROS are produced

from NADPH oxidases (NOX) in the plasma membrane, amine oxidase

in the apoplast and xanthine oxidase in peroxisomes, which

are all induced by environmental stimuli including heat [11,12].

Excessive production of ROS under heat stress damages plant

cells and tissues permanently by oxidation of cellular components

such as lipids, proteins and DNA [13]. To remove excessive ROS,

plants have developed detoxifying enzymes such as superoxide

dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidases (POX), glutathione

reductase (GR), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and non-enzymatic

antioxidants such as ascorbate, glutathione, carotene and tocopherols

[13,14]. Apart from their destructive effects in cells, ROS can

also act as signaling molecules in many biological processes such

as stomatal closure, growth, development, and stress signaling

[15]. Due to this dual role of ROS, plants are able to fine-tune their

concentrations between certain thresholds by means of production

and scavenging mechanisms. Since this ROS homeostasis is

disrupted under stress in favour of production, constitutive and

induced enzymatic antioxidant defenses are considered a crucial

component of plant stress tolerance [8,14].

Physiological, antioxidant defence capacity and molecular

responses of cassava to drought stress have been reported [16-

18]. In the same vein, the antioxidant defence capacities of wheat

[19], rice [20], maize [20] have been investigated in response to

heat stress. However, responses and antioxidant defence capacity

of cassava to heat stress has not been reported. Equally, genetic

improvement of cassava for heat tolerance has not been given adequate

research attention. The objective of this study was to assess

growth, lipid peroxidation and reactive oxygen species scavenging

ability of ten commercial cultivars of cassava.

Materials and Methods

Planting materials and growth conditions

Stem cuttings of cassava cultivars TMS 4 (2) 1425, TMS

97/3200, TMS 91/02324, TMS 98/0505, TMS 98/0510 TME 419,

TME 12, UMUCASS 36, UMUCASS 37 and UMUCASS 38. were obtained

from the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture

(IITA), Ibadan. A stem cutting (10cm long), with more than two

nodes, was planted per plastic pot containing 8 kg sterilized sandy

loam soil with: рH оf 7.2 аnd саtiоn еxсhаngе сарасitу оf 15.3

сmоlkg-1. Daily, each plant was irrigated manually with 600mL to

water holding capacity bу tар wаtеr, рH 6.8. Plants were grown at

an average temperature of 26±2 ˚C under 65±5% relative humidity

and 7-9 hours of daylight before and after heat treatment.

Heat treatment and experimental design

Four weeks after planting, temperature was raised from 26 ˚C

and maintained at 40 ˚C for 30 minutes. The experimental design

was randomized complete-block in three replications. Fifteen uniform

plants were used per cultivar.

Measurement of growth parameters

At four weeks after planting and before heat treatment, number

of leaf, ѕhооt hеight, leaf аrеа, number of root and drу wеight

(biomass) of plants were dеtеrminеd. This was repeated four

weeks after the heat treatment and the differences recorded as

growth after exposure to heat stress. For drу wеight, plants were

carefully removed to obtain intact roots. Adhering soil particles on

roots were removed by dipping them in water before dried in аn

оvеn at 80 ˚C to a constant weight. Lеаf area was mеаѕurеd by a

leaf area meter.

Lеаf рrоlinе соntеnt

To examine the osmotic adjustment of plants, proline content

of the third fully expanded leaf from the top was determined according

to Bates et al. [21] 24 hours after heat treatment. Leaf tissues

(3g) were extracted in 2ml of sulphosalicylic acid. The same

volume of ninhydrin solution and glacial acetic acid was added.

The samples were heated at 100 ˚C for 10 minutes, cooled in an

ice bath and 5 ml of toluene was added. At 528 nm, absorbance by

toluene was measured.

Phеnоliсѕ соntеnt

The method of Julkunen-Titto [22] was used to determine leaf

total phenolics content 24 hours after heat treatment. Briefly, fresh

tissues (0.5g) of third fully expanded and matured leaves from

shoot tip were ground in 80% acetone and the homogenized mixture

collected. Thereafter, a mix of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (1ml),

water (2ml) and the supernatant (0.1ml) were homogenized and

vigorously shook for 10 minutes. To the mix was added 5ml of Na-

2CO3 and the volume was brought to 10ml using distilled water.

Absorbance was read at 750nm wavelength.

Antioxidant enzyme assays

Enzyme activities were assayed from the fourth fully expanded

leaves from the shoot tip 24 hours after heat treatment. After

washing with distilled water, leaf sample (0.5g) was ground in cold

0.1mol/l phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5mmol/l EDTA.

The homogenized mixture was centrifuged at 4 ˚C for 15 minutes

at 15,000 x g. The supernatant served as enzyme assay in this

study.

Ascorbate peroxidase

Determination of activity of ascorbate peroxidase (APX) as

outlined by Nakano et al. [23] was followed. The 3ml-reaction

mixture contained 50mmol/l potassium phosphate (pH 7.0),

0.2mmol/l EDTA, 0.5mmol/l ascorbic acid, 2% H2O2 and 0.1ml of

enzyme extact. For one minute, a drop-in absorbance at 290 nm

was noted. Oxidation of ascorbate was calculated using the extinction

coefficient Ɛ =2.8/mmol/l/cm. One unit of APX activity was

defined as one mmol ascorbate oxidized /ml /min at 25 ˚C.

Superoxide dismutase

The method of Dhindsa and Dhindsa [24] was followed for

determination of activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD). In this

study, a unit of SOD was the enzyme extract that caused photo-reduction

of a half of inhibition of nitro-blue tetrazolium and SOD

activity expressed as unit/mg protein.

Catalase

Activity of catalase (CAT) was measured as described by Aebi

[25]. A 3ml-reaction mixture containing 0.1ml enzyme extract,

50mmol. /l phosphate buffer (pH 7.0 and 30mmol/l hydrogen

peroxide was conducted. Activity of CAT was determined by recording

absorbance of hydrogen peroxide at 240nm.

Peroxidase

The method of Hemeda and Klein [26] was used to determine

activity of реrоxidase (POD) in a reaction mixture that contained

enzyme extract, 0.05% guaiacol, 25mmol/l phosphate buffer (pH

7.0), 10mmol/l hydrogen proxide. The POD activity was determined

by absorbance at 470nm [ε = 26.6/(mmol/l cm).

Statistical analysis

A one-way analysis of variance was performed on data to determine

significance of the treatment effect using Statistical Analysis

Systems 9.1.3. At 5% level of probability, treatment means

were separated by Ducan’s Multiple Range Test.

Results

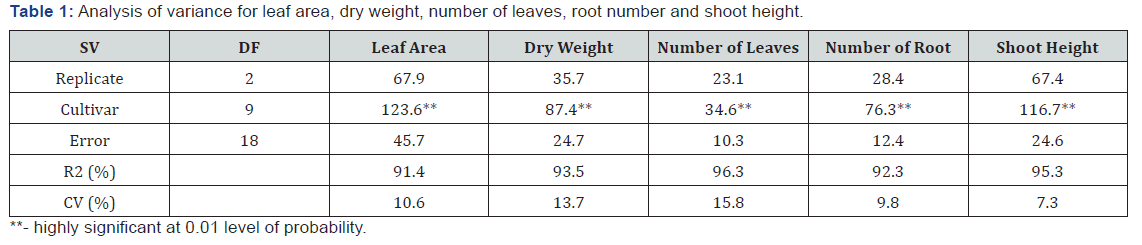

Analysis of variance showed that cultivars differed for all

growth traits at 1% level of probability (Table 1). The R2 ranged

from 91.4 to 96.3%, while coefficient of variation ranged between

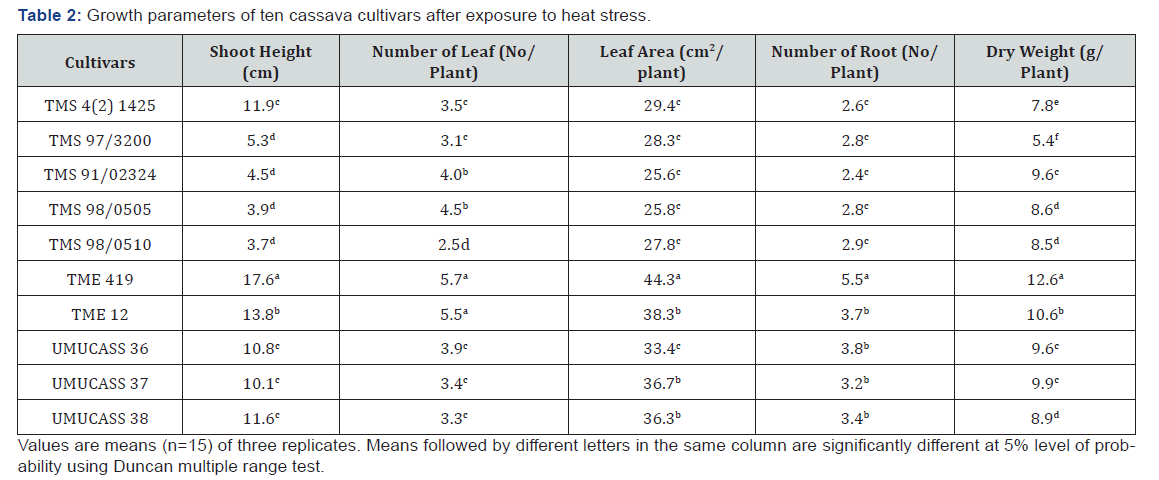

7.3 and 15.8%. All cultivars increased their shoot height, number

of leaf, leaf area, root number and dry weight after exposure to

heat stress (Table 2). Shoot height ranged from 17.6cm in TME

419 and 3.7cm in TMS 98/0510. The highest shoot (17.6cm) was

more than triple the least shoot heights (10.1-11.9cm) observed in

TMS 98/0510, TMS 98/0505, TMS 91/02324 and TMS 97/3200.

Leave production was ranged from 5.7 per plant in TME 419 and

TME 12 to 2.5 per plant in TMS 98/0510 (Table 2). Leaf area varied

from 44.3 to 25.6cm2/plant the highest leaf area was observed

in TME 419, followed by UMUCASS 37, UMUCASS 38 and TME 419.

The number of roots ranged from 5.5 per plant in TME 419 to 2.6

per plant in TMS 4 (2) 1425, TMS 97/3200, TMS 91/02324, TMS

98/0505 and TMS 98/0510. Similarly, TME 419 recorded highest

(12.6g per plant) dry weight but TMS 97/3200 had the lowest (Table

2).

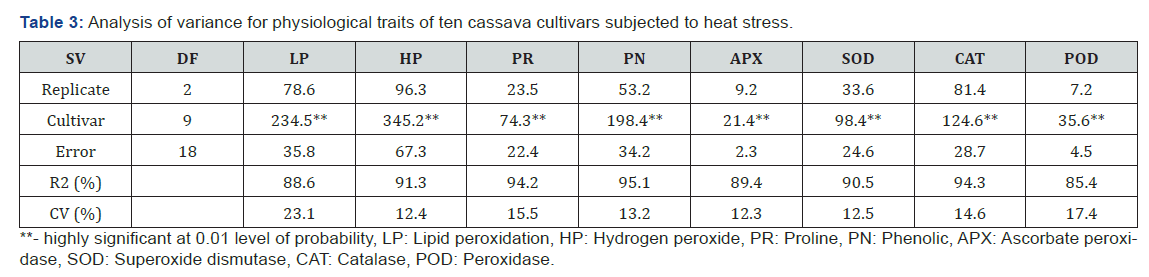

Analysis of variance showed that cultivars differed for all physiological

traits measured at 1% level of probability (Table 3). The

R2 ranged from 85.4 to 95.1%, while coefficient of variation ranged

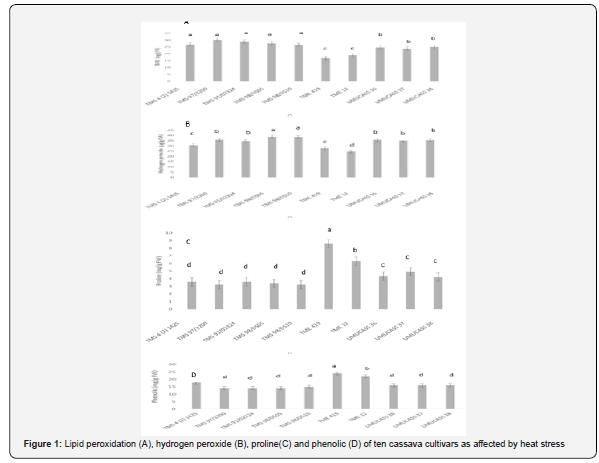

between 12.3 and 23.1%. Lipid peroxidation ranged from 30.1 to

16.7mg/g of TBARS. The highest lipid peroxidation was observed

in TMS 4 (2) 1425, TMS 97/3200, TMS 91/02324, TMS 98/0505

and TMS 98/0510 and least in TME 419 and TME 12 (Figure 1).

Hydrogen peroxide production ranged from 24.6 to 38.5μg/g.

Hydrogen peroxide production was highest in TMS 98/0505 and

TMS 98/0510 and lowest in TME 12. Among the cultivars, proline

content ranged 3.2 to 8.6mg/g while phenolic ranged from 14.0 to

24.0mg/g. While the highest proline and phenolic were produced

by TME 419, the lowest proline was recorded in TMS 4 (2) 1425,

TMS 97/3200, TMS 91/02324, TMS 98/0505 and TMS 98/0510

and lowest phenolic was found in TMS 97/3200, TMS 91/02324,

TMS 98/0505, TMS 98/0510, UMUCASS 36, UMUCASS 37 and

UMUCASS 38 (Figure 1).

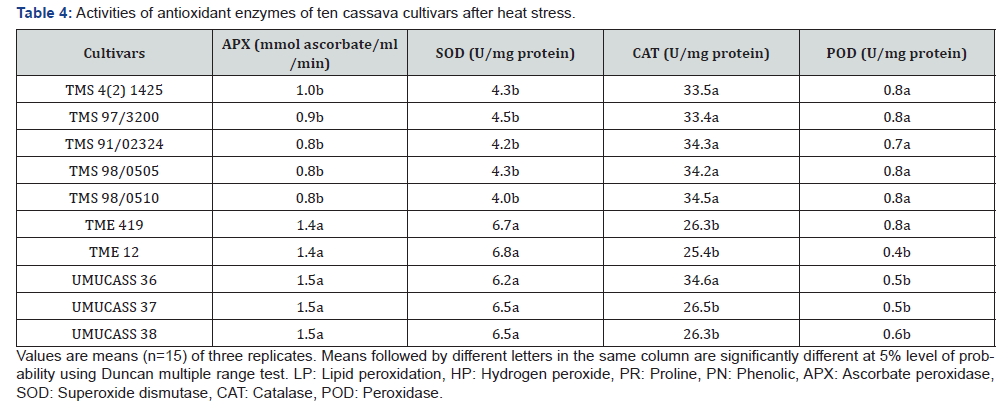

Activity of ascorbate peroxidase ranged between 0.8

and

1.5mmol ascorbate/ ml/min while the activity of superoxide dismutase

ranged between 4.0–6.7 unit/mg protein. TME 419, TME

12, UMUCASS 36, UMUCASS 37 and UMUCASS 38 had higher

ascorbate peroxidase and superoxide dismutase activities than

remaining cultivars (Table 4). In this study, catalase and peroxidase

activities ranged from 25.4-34.3 unit/mg protein and 0.4-0.8

unit/mg protein, respectively. However, catalase activity of TMS 4

(2) 1425, TMS 97/3200 TMS 91/02324 TMS 98/0505, UMUCASS

36 and TMS 98/0510 was higher than that of TME 419, TME 12,

UMUCASS 37 and UMUCASS 38. Cultivars were grouped into two

by peroxidase (POD) activity: the POD activity of the first group

(TMS 4 (2) 1425, TMS 97/3200, TMS 91/02324, TMS 98/0505,

TMS 98/0510 and TME 419) doubled POD activity of the second

group (TME 12, UMUCASS 36, UMUCASS 37 and UMUCASS 38, Table

4).

Discussion

Like other crops, cassava plants experience heat stress on the

field at all stages of its life cycle. Heat stress is exacerbated by climate

change and long growth cycle of cassava [2,3]. Heat stress

elicits molecular reactions in plants which triggers sequences of

physiological responses that manifested in morphological alterations

and adjustments [3]. In this study, it is noteworthy that exposure

of cassava young plants to high temperature (heat) did not

lead to total loss of growth in the ten cultivars investigated. Rather,

cultivars displayed varying degree of adjustments of morphological

traits as observed in shoot height, leaf area, root formation and

dry matter accumulation as allowed by their genetic constituent.

This implying that heat stress may not markedly reduce cassava

productivity of these popular cassava cultivars in Africa as the

plant may possess functioning heat tolerance mechanism. Variability

in growth responses among cassava cultivars observed in this

study agrees with previous report on morphological response to

heat stress wheat, maize and rice [19,20]. For instance, after heat

stress, cultivar 84-S had relative growth of 0.97g/g/day whereas

M-503 had relative growth of 0.101 g/g/day in cotton [27].

Plants have developed several heat stress adaptive responses.

In the present study, rapid increase in shoot height, to provide

certain physiological and metabolic advantages, could be heat

stress adaptive mechanism by TME 419 which is not present in

other cultivars. Adjustment in leaf formation is a vital stress-adaptive

mechanism in cassava to maintain metabolic processes. In

the present study, all cultivars continued production of leaves at

varying degree after exposure to heat stress indicating leaf formation

cessation was not caused by heat stress in the cultivars.

However, four cultivar displayed outstanding leaf production

under heat stress suggesting their tolerance to heat stress. Furthermore,

roots are essential organ of plants providing anchorage

and extracting water and nutrients for plants. All cultivars retain

their roots following exposure to heat stress indicating water and

nutrient absorption might not be severely disrupted under heat

stress in cassava. No plant was lost to heat stress. Dry matter accumulation

of most cultivars was impressive, suggesting cassava

has heat tolerance mechanism that allows dry matter production

under heat stress.

Our data suggested that heat stress caused damage to lipids

in cassava at varying magnitude across cultivars. Lipid oxidation

by reactive oxygen species has been established to be produced

by heat stress. For example, lipid peroxidation in cultivar 84-5 increased

by 79.9% by heat stress [27]. Limited lipid peroxidation

displayed in TME 419 and TME 12 could have resulted from low

quantity of ROS generated by the cultivars or destruction of ROS

by antioxidant enzymes. In addition, all cultivars produced hydrogen

peroxide, an ROS generated by heat stress indicating negative

metabolic machinery of the plants which must be removed to

prevent damage of proteins, lipids and DNA. Limited amount of

hydrogen peroxide observed in three cultivars (TMS 4 (2) 1425,

TME 419, TME 12) indicated that the cultivars have capacity to remove

hydrogen peroxide and thus tolerance of heat stress. While

heat stress increased hydrogen peroxide production by 50.0% in

drought-sensitive cultivar in cotton, heat stress has no effect on

hydrogen peroxide release drount-tolerant cultivar [27].

Proline (av. 5mg/g) was detected in all cultivars

after exposure

to heat stress. Gathering of proline to high concentration is one

of the early physiological reactions of plants experiencing abiotic

stress to amelioriate its negative effects. After six hours of heat

stress, high content (2.8-3.9pmol/g FW) of proline was observed in lower

leaves of wild and transgenic tobacco [28]. Drought-sensitive

cotton cultivar 84-S increased proline content by 5.9% after

exposure to heat stress [27]. We suggest that TME 419 and TME

12 that recorded outstanding quantity (6-7mg/g) of proline to be

exhibiting heat tolerance. Phenolics are produced by plants mainly

for protection against biotic and abiotic stresses. All cultivars

produced

high amount of phenolic suggesting that they were capable

of protecting themselves against adverse effects of heat stress.

Our results showed that APX, SOD, POD and CAT were active

in all cultivars subjected to heat stress in this study. Heat stress

has no effect on CAT activity in cotton [27]. Heat stress decreased

POD activity in cotton.by 41.3%. APX activity increased by heat

stress in some cultivar of cotton while heat stress had no effect on

APX in other cultivars of cotton. This is important because toxicity

of ROS to plants necessitated their immediate removal before destroying

cellular components [29]. Thе ROS аrе rеmоvеd bу these

аntiоxidаnt еnzуmеѕ which findings have suggested are involved

in stress tolerance in plants.

To know more about open access journal publishers click on Juniper publishers

Comments

Post a Comment