Factors Influencing Zai Pit Technology Adaptation: The Case of Smallholder Farmers in the Upper East Region of Ghana-Juniper Publishers

Journal of Agriculture Research- Juniper Publishers

Low agricultural productivity resulting from low

erratic rainfall, high evaporation, and deteriorating soil fertility

among farmers in the upper East region has led to a mission for

sustainable production practices with greater resource use efficiency.

To lessen water stress and reduce runoff rains, water harvesting

technologies like the zai pit technology is an alternative option whose

influence on agricultural productivity cannot be under estimated. This

study therefore seeks to assess the influential factors of zai pit

technology adaptation among 296 smallholder farmers in the Upper East

region of Ghana. Out of the 296 sampled population 155 respondents were

adopters of the technology already while 141 were not. The study used

binary logistic regression to analyses the factors influencing the

adoption of zai pit adoption among farmer. The results from the studies

shows that socio-demographic characteristics of farmers such as,

farmer‘s age, years of experience, number of non-formal trainings

attended, beneficiaries of NGOs, and membership of associations, were

significant and plays an important role in farmers adaptation of zai

pits technology. On the contrary variables like, land size, sloppiness

of land, household size, holding of formal title to land and used of

improved planting materials were not significant variable to farmer’s

adaptation of the zai pit technology in the study area. Based on the

results it was recommendations that farmers should be encouraged to join

farmer groups or association and also attend non- formal training on

agricultural practices to improve adoption and utilization of zai pits.

Keywords: Binary logit; Smallholder farmers; Upper east; Zia pit technology

Abbreviations:

EPA: Environmental Protection Agency; GDP: Gross Domestic Products;

SPSS: Statistical Packages for Social Sciences; ICARDA: International

Center for Agricultural Research on Dry Areas; NARS: National

Agricultural Research System; SWC: Soil Water Conservation; TAM:

Technology Acceptance Model; PU: Perceived Usefulness; PEOU: Perceived

Ease-of-Use

Introduction

Low soil fertility is a major limitation to rain fed

agriculture among smallholder farming in Africa [1]. Nutrient depletion

and inadequate water in the soil of most African countries for some time

now has transformed originally fertile lands that could yielded between

2t ha-1 and 4t ha-1 of cereal grain, into infertile lands where cereal

crops yields less than 1t ha-1 [2]. Insufficient water couple with soil

infertility is a major drawback to rain fed agriculture among

smallholder farming in Africa [1]. To be able to restore soil to

sufficient level of fertility, water harvesting techniques and improved

soil fertility management technologies should be promoted among the

smallholder framers. The soil fertility interventions include use of

mineral fertilizer and organics such as animal manure and green manure

among others [3]. The use of these technologies enable farmers to deepen

their production and thereby increase economic benefits due to

increased yields.

Water as identified to be one of the important

factors that facilitates plant growth needs to be sustained in the soil

to improve plant growth. Soil moisture method farmers can adopt

includes, macro and micro catchment technologies and rooftop harvesting

technologies. Micro-catchment is a method of collecting runoff rains

near the growing plant and replenish the soil moisture which are

generally used to grow plants like maize, sorghum, groundnuts and

millet. The micro-catchment methods includes zai pit, also known in

Niger as Tassa and in Mali as Towalen, which has been identified as one

of the successful interventions that improve rainfall capturing and

lessen runoff and evaporation, and in a long run improves agricultural

productivity [4].

Zai is a term that refer to small planting pits that

typically measure 20-30cm in width, are 10-20cm deep and spaced 60-80cm

apart. Zai is an ancestral practice to regenerate degraded and crusted

soils by breaking up the surface crust to improve water infiltration. It

is a traditional land rehabilitation technology to

rehabilitate degraded drylands and to restore soil fertility to the

benefit of farmers living in drylands. The technique was adopted

to reclaim severely degraded farmland that water could not penetrate.

This technology is mainly applied in semi-arid areas on sandy/

loamy plains, often covered with hard pans, and with slopes

below 5% [5].

The application of the zai technique can increase production

by about 500 % if well executed [6]. Sawadogo [7], explained that

pits have been used to diversify plants biomass in Burkina Faso

and the practice has help improve soil fertility and crop yield in

the area. The zai pit is most suitable for cultivated lands characterized

by crusted soils, hardpan formation, compaction, inadequate

ventilation, reduced penetrability and limited plant root development

[8]. With these characteristics pit digging enables more

water penetration and runoff water is trapped due to the earthen

bund formed downslope of the pits [9]. Zai pits are especially relevant

to areas receiving 300-800mm annual rainfall [10]. Higher

rainfall amounts could cause water-logging of the pits. Zai allows

collecting 25% of a run-off coming from 5 times its area [11].

One of the major constraints to agriculture development in

the Upper East Region of Ghana is land degradation due to desertification.

Mr. Asher Nkegbe, the Regional Director of the Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA) due to this problem introduced

the zai pit technology as a new sustainable water harvesting technique

intervention in the region. This provides a window of opportunity

for farmers to improve crop performance in this harsh

and changing climate. The future seems brighter for the farmers

and their families, says Mr. Nkegbe.

Materials and Methods

Study area

This study was conducted in the upper east region of Ghana,

the studies was narrowed to two districts where the zai pit technology

was introduced first in the region. The two districts were

the Kassena-Nankana West district and the Talensi district. Kassena-

Nankana West District is one of the thirteen districts in the

Upper East Region of Ghana. It is located approximately between

latitude 10.97° North and longitude 01.10° West. It has a total land

area of approximately 1,004sq. km. The District falls within the

interior continental climatic zone of the country characterized by

dry and wet seasons. The Talensi district was part of the Talensi-

Nabdam district in the Upper East region. The separate Talensi

district was created in 2012 with Tongo as the capital. The district

lies between latitude 10o 15’ and 10o 60’ North of the equator and

longitude 0o 31’ and 1o 05’ West of the Greenwich meridian. It has

a land area of 838.4km2.

In the rural localities of these two districts, nine (9) out of ten

(10) households (93.4%) are agricultural households while in the

urban localities, 75.4 percent of households are into agriculture.

Most households in the district (98.2%) are involved in crop farming.

Crop farming, animal rearing and hunting are the main economic

activities in the two districts. Agriculture is mainly rain fed

with little irrigation and serves as the main source of employment

and account for 90.0 percent of local Gross Domestic Products

(GDP). The main agricultural produce are groundnuts, sorghum,

millet, rice and maize.

Sampling strategy

This study used primary data collected through questionnaire

from smallholder farmers in the Upper East region of Ghana.

The purposive stratified sampling was adopted in household interviews

to ensure representative adopters and non-adopters of

the technology were sampled within the area of study. The study

makes use of the [12] sample size determination formula to determine

the sample size. That is

Where, n = sample size

t = value of selected alpha level of 0.025 in each tail = 1.96 for

95% (that is the alpha level of 0.05 which indicates the level of

risk the researcher is willing to take, the true margin of error may

exceed the accepted margin of error).

Z = proportion of population of farmer engaged I the zai technology.

h = proportion of population of farmer who are not engaged in

the zai technology.

d = accepted margin of error for proportion begin estimated=

0.05 (error researcher is willing to accept).

The first stage of data handling involved data cleaning. The

data was first of all cleaned by examining the questionnaire to

ensure they were complete and had been consistently filled. The

household survey data was analyzed by the use of Statistical Packages

for Social Sciences (SPSS) software. The study employed

analytical techniques like descriptive statistics and binary logistic

regression. Descriptive statistics such as frequency tables,

percentages mean and standard deviations were used to analyze

farmers’ socio-economic characteristics. Chi - square analysis was

employed to test the relationship between farmers ‘socioeconomic

characteristic and adoption of zai pits technology. To ascertain

the differences of means between adopters and non-adopters, the

statistically significant paired t- tests was used. Binary logistic regression

was used in zai pit adoption model to determine factors

influencing adoption of zai pits. That is

Where;

K= is the probability of adopting zai pits

(1-K) = is the probability that a farmer does not adopt zai pit

α = y intercept

β = regression coefficients

e = error term

1 10 x − x = independent variables

The independent variables were the socio – economic characteristics

as shown below;

X1 = Household size

X2 = Non – Formal Training

X3 = Member of association.

X4 = Total Farm Size

X5 = Sloppy Land

X6 = Formal Title

X7 = Used Improved Planting Material

X8 = Farmers experience

X9 = Beneficiary of NGO.

X10 = Age of farmer

Review of related literature

Water scarcity impact on agricultural productivity: One of

the major impediments to rain fed agricultural in arid and semi-arid

areas is scarcity of water. Low productivity in arid and semi-arid

areas are credited to marginal and unpredictable rainfall, worsened

by high runoff and evaporation loose among other factors

[13]. Unpredictable rainfall and droughts are included in the influential

factors of agricultural production among smallholder

farmers mostly in rural areas [14]. The mainstream of agricultural

lands in Africa are arid and semi-arid lands as a result effort to

increase productivity of rain-fed system in these areas is a step

in the right direction. Several water harvesting techniques alongside

irrigation systems should be adopted by farmers to improve

water moisture deficit in arid and semi-arid areas, since there is

a promising increase in productivity if the soil moisture is maintained.

The best way to deal with water scarcity challenge which

is a major threat to food security, is to embrace water harvesting

techniques to manage water for rain-fed agricultural [15].

A number of case studies by the International Center for Agricultural

Research on Dry Areas (ICARDA) affirmed that productivity

gaps can be reduced by engaging in improved soil and water

management practices by farmers [16]. Improved water management

in the long run serves as a catalyst for economic growth

among farmers in arid and semi-arid areas since the productivity

of farmer will increase. Numerous researchers has come out with

ways to address the challenge of water scarcity to enhance productivity,

among their suggested water harvesting techniques are

the zai pits, negarims, semi-circular bunds and half-moons [17].

This study focuses on the zai pit technique technology as a water

harvesting technique in the most sim-arid area in Ghana.

Definition of zai pit technology

The zai pit technology originated from Burkina Faso, although

some scholars trace it origin to Dogon in Mali [18]. “Zai” in Burkina

Faso, refers to small planting pits typically measuring 20-30cm

in width, 10-20cm deep and spaced 60-80cm apart. There are

different names ranging from counties to countries, for instance

it is known as “tassa”, “towalen” in Niger and Mali respectively.

However, the English term used for this pit includes “planting

basins”, “micro pit” and “small water harvesting pits”. Zai pits are

most relevant in areas that receives 300-800mm rainfall annually

[10]. Zai pits technology has caught the attention of many NGOs

and for that matter intensive campaign is embarked on it adoption

in Zimbabwe and other parts of Africa [19]. Zai pit technology is

practiced in Niger [20], South Africa [21], Zambia [22,23], Ethiopia

[24] and recently in Ghana. [25] recognized how the central

plateau of Burkina Faso experienced major improvement in millet

and sorghum productivity from around 400kg ha-1 in 1988 to

650kg ha-1 in 1996-2000. The rise was mainly due to improved

soil and water preservation as well as addition aspects of ISFM. In

Ghana, the zai pit technology is currently practiced in the upper

east region of the country, which was introduce by the Director of

the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). During the inception

of this technology, about 100 farmers from selected communities

like Kazugu, Kayilo, and Kulia Yiduriand Wuug embraced the technology

and participated in it. Report from some participant like

Thomas Aluah, Apiato Masumdok and Pastor Michael Tamponab

just to mention but few testified to it that the technology has help

them increase their productivity and were welling to continue it

practice.

Factors that influence the farmers adaption of zai pits

technology: Adaptation and utilization of water harvesting techniques

is one of the important conditions, for agricultural development

especially in the arid and semi-arid areas. Despite the

technologies developed and tested on farms by the National Agricultural

Research System (NARS) to reduce the effects of water

scarcity in semiarid areas, farmer’s adaptation remains low rendering

continuous low productivity [17]. Factors inducing zai pits

adaptation vary from place to place and from household to household

due to differences in socio-cultural, economic and biophysical

conditions [26]. Slingerland & Stork [27], examined determinants

of practice of zai and mulching in north Burkina Faso and

they found that farmers applying zai pits had larger households,

more means of transport and more livestock, which is consistent

with their need for manpower and manure.

Wildemeersch et al. [28] identified that, lack of

enough knowledge

on erosion and other key resources such as manure, agricultural

equipment and transport facilities limit the application of zai

pit technology in Tillaberi Niger. In northern Burkina Faso, [29]

found that, variables like education and perceptions of soil degradation

were bases for the adoption of zai technique. Ndah et al.

[30] also found out that, the great potential adoption of zai pits

displayed by farmers from Malawi and Zambia case relates to positive

institutional factors such as well-structured extension system

and integration of the lead farmer approach [31]. The above studies

emphasis on farmers ‘characteristics and resource availability

to describe adoption problems in different regions. However, in

Ghana research on factors influencing farmers ‘adoption of zai pits

is scanty, therefore it will not be prudent to infer the results of

the above studies in Ghana. Furthermore, zai pits have their own

unique characteristics and requirements different from other rain

water harvesting technologies hence it is important to establish

factors that influence its adoption.

Socio-economic factors and adoption of zai pit technology

to enhance food security: The studies of [32], revealed that

low uptake of improved technologies and incorrect soil fertility

management practices compromise sustainability and food security

among smallholder farmers. The driven force of agricultural

growth of any nation is high outputs to farmers’ production. To

increase the productivity of farmer, a larger number of farmers

are expected to adopt improved agricultural technologies that

increase productivity and also be more efficient in the use of resources

like land and water in an environmental sustainable manner

(World Bank Group, FAO and IFAD, 2015).

Adekambi, Diagne, Simtowe, & Biaou [33] is also of the view

that different variables such as age and education affect adaptation

of agricultural technologies either positively or negatively. He

found out in his studies that, higher education influence adoption

decision positively since it is associated with ability to synthesis

more information on technologies that are on offer and this leads

to improvement of the general management of the farm. On the

other hand, more education can also lead to individuals having

more available occupation option thereby spend less time to attend

to this farm activities affecting adoption of agricultural related

technologies negatively.

The number of hours involve in digging a zai hole has also

been another influential factor to its adaptation. Barro & Lee [34]

noted that it takes about 300hour/ha to dig the zai pit, whiles [9]

assert that 450hours/ha is involved in digging the zai pit plus another

250hour/ha to apply fertilizer in the holes, hence the zai pit

is more suitable when practiced by a group of farmer together instead

of individual farmers. This means wealth farmer are more

likely to benefit from this technology since they can employ more

laborers to work for them.

Murgor, Saina, Cheserek, Owino, & Sciences [35] found that,

financial issues like cost of hired labour, transportation cost, construction

cost etc. are limitations for farmers to adopt improved

agricultural technologies. It is difficult to increase agricultural

productivity without credit facilities, with the fact that most farmers

are poor in resource. Another expects, higher investment and

management in livestock leads to increased readiness of dung.

Better-quality livestock keeping brings revival of indigenous foliage

and greater accessibility of fodder [36]. Research findings indicates

that rainwater in Africa is at 127mm yr-1 contrary to North

America’s 258mm yr-1, South America’s 648mm yr-1 and global

mean of 249mm yr-1 [37].

Impact of zai pits technology on output of farmers: Research

has revealed that, zai technology escalates crop yields and

straw (residue) production on highly degraded soils and helps

to lessen the opposing effects of dry spells, which are frequent

during the cropping period in the dry land areas [9,38]. A study by

[9] revealed that, zai pit technology increased sorghum yields by

310kg ha-1 as compared to the non-zai pit situation in the village of

Donsin. Zai pits technology (also known as Tumbukiza) produced

significantly higher dry matter yields than conventional method in

Western Kenya [39]. In semi-arid areas, a drought can lead to total

crop failure but experience from Zambia [22] shows that, planting

basins can improve the possibility of maintaining some production

with very low rainfall. During an impact assessment of Soil

Water Conservation (SWC), agroforestry and agricultural intensification

in 5 villages on the northern part of the Central Plateau of

Zambia, farmers agreed unanimously that soil water conservation

(SWC) and in particular zai had a positive impact on household

food security [36]. In West Africa, [40] found that, the use of zai

alone would not improve much the productivity (only 200kg ha-1

of sorghum grain) but when the zai is associated with manure and

fertilizer large crop yield increases can be obtained (1700kg ha-1

of sorghum grain). Again, in Niger manure application with zai

showed a 2-69 times better grain yields than zai pit with no nutrient

amendment [38].

Theoretical framework

Technology acceptance model (TAM): This is the commonest

and most used model of acceptance and use of technology [41].

It was developed by Fred Davis and Richard Bagozzi with its main

assumption as, when a person intends to act, they will be free to

act unhindered [42]. However, in reality and practical acceptance

and adoption is constrained by limited ability (such as cognitive,

psychomotor or materials), time environmental or even unconscious

habits that hamper the autonomy to act. The model assert

that when users are faced with a novel technology, the choice

about how and when to apply that technology is influenced to a

large extent, the perceived usefulness (PU) which was described

by [42] as “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular

system would enhance his or her job performance”, and the

perceived ease-of-use (PEOU) also been described as “ the degree

to which a person believes that using a particular system would be

free from effort” [42].

According to [43], both PEOU and PU are subject to

external

variables mainly social factors, cultural factors and political factors.

The social factors are language skills and enabling conditions,

whiles political factors are the effects of the technology use

on politics and political crisis. Attitude is about the user of the

technology evaluation of the attractiveness to employ a certain

technology. Behavioral intention is the measure of the probability

of an individual to apply the technology. Technology Acceptance

Model (TAM) enables understanding of the role of perception on

usefulness and ease of use in determining the desire to apply the

technology and the level to which the technology will be adopted.

Additional, external variable affects the behavioral intention to use

and the actual usage of the technology given their indirect

effect on PEOU and PU.

To make use of the two models, this study proposes that

technology adoption is a multifaceted, inherently social, developmental

process, individuals create distinct yet flexible views of

the technology that affect their adoption choices. The adoption is

influenced by the perception of the inherent features of the technology,

social-economic factors like educational level, involvement

of males in the process of adoption and post-implementation extension

services offered to the farmers to determine the extent of

consequent spread.

Roger’s innovation diffusion theory: Rogers’s doctoral dissertation

in 1957 which study’s rural and agricultural sociology,

focusing on the trends of use of new weed spray by Iowan farmers.

Rogers made an appraisal on related findings on the way people

embraced a new technology or idea; studies in varied disciplines

such as medicine, agricultural and marketing, at the end he realized

so many similarities and he used it to formulate an all-embracing,

theoretical framework.

According to Rogers innovation can be define as a new object,

idea, technology, or practice. Innovation can either be tangible,

physical objects like new device or machine or intangible objects

like a new design method or educational method. Also, the concept

of innovation originality could relate to both place and population.

This model is general in nature giving it extensive application.

Diffusion can also be defined as the spatial and temporal

movement of the new technology to different economic units. Kaminski

[44] put a difference between adoption and diffusion by

defining diffusion (aggregate adoption) as the process in which

a technology is transferred through various channels over time

amongst the members of a community. He identify four elements,

firstly, the technology that is the new idea, practice or object being

spread, secondly, communication channel which represent how

information on the new technology move from change agent (extension,

technology suppliers) to the final consumers or adopters

example farmers, thirdly, the time period over which a technology

is adopted in a social system and lastly, the social system.

On the other hand, Rogers emphasize that adoption is where

someone (farmer) is motivated to either using or not to use a novel

technology at certain period of time. Feder et al. [45] also differentiated

between individual (farm level) and aggregate adoption.

They are of the view that, individual adoption is the degree of use

of a new technology (innovation) in the long-run where the individual has adequate information on the new technology and it’s

potential whereas aggregate adoption is measured by the aggregate

level of use of a given technology within a given geographical

area. Ruttan [46], also described aggregate adoption as the spread

of a new technique within a population. The difference between

adoption and diffusion is essential for theoretical and empirical

evaluation of the levels of the two economic phenomena. Kaminski

[44] and Mahajan & Peterson [47], brought reasons for the

process of attaining information and the time intervals created in

respects to the rate of adoption by people (farmers) in the society

(Figure 1).

Based on the theoretical framework, the study was guided

by the above conceptual framework. Erratic rainfall experienced,

high temperature which causes evaporation and bad farming

practices has rendered almost all the land in the study area infertile

with little water sustain in them. These problems leads, to

low productivity since the nutrient and water in the soil are not

enough to support plant growth. This situation calls for an intervention

to eradicate the problem hence the adaption of the Zai pit

technology, which helps to sustain water in the soil for a long time

and also increases soil fertility when combined with organic or inorganic

substances. Zai pit technology is the dependent variable.

Adoption of the Zai pit technology is influence by independent

factors like the socio-economic factors, perceptions farmers have

about the technology and external factors like government policies

on water harvesting techniques which the farmer has no or

little control over it.

Results and Discussion

Factors influencing zai pit technology adaptation

Out of the 296 farmers interviewed for the studies, 72.6%

representing 215 farmers were males and the remaining 27.4%

representing 81 farmers were females. The number of farmers

who were adopters were slightly higher than the number of farmers

who were non-adopters of the technology with percentages

of 52.4% and 47.6% (155 and 141) respectively. About 103 farmers

representing 66.5% out of the adopter were males with only

52 farmers representing 33.5% were females. In the case of the

non-adopter the number of females was 29 respondents representing

20.6% and 112 respondents representing 79.4% were

males. Buyu [48], is of the view that gender difference is one of the

determinants of choice of soil conservation and water harvesting

technique. Gender difference is known to determine the choice

of soil conservation and water harvesting technique [48]. Women

base their choices in terms of the opportunity cost of realizing

better yields while men consider cost related matters such as labor

and time requirements [48]. This is probably because female

famers are equally committed as male farmers to find mitigation

measures to food insecurity and overall improvement of their families

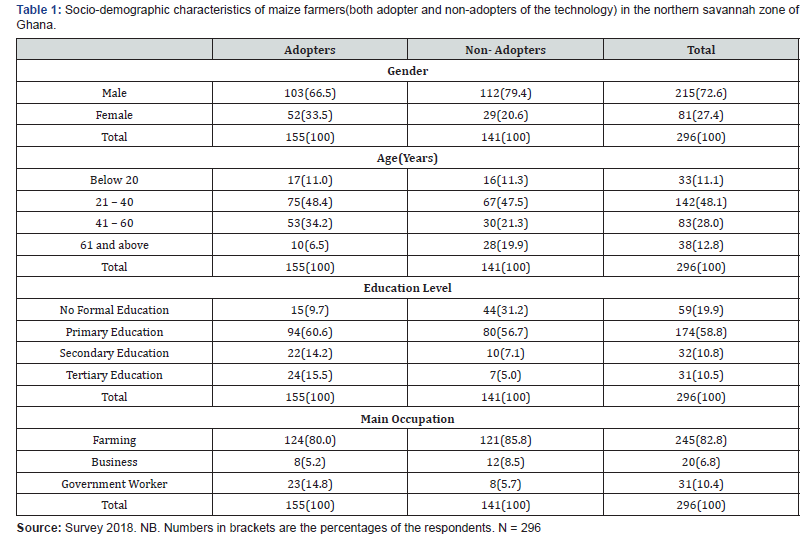

‘wellbeing (Table 1).

Majority of the farmers (174 farmers) with a percentage of

about 58.8% had attain primary education out of which 94 respondentss

were adopters and 80 respondents were non-adopters.

Respondents with tertiary education recorded the least the

number with 31 respondents standing for 10.5% of which out of

this number, 24 respondents representing were adopters and 7

respondents were non-adopters. Respondents with no formal education

recorded 19.9% which represent 59 respondents out of

this 15 were adopters whiles 44 were non-adopter. Those with

secondary education recorded 10.8% standing for 32 respondents

out of these 22 respondents were adopters whiles 10 respondents

were non-adopters. These studies are consistent with the work of

[49], who found out in his studies that, higher education influence

adoption of decision positively since it is associated with ability

to synthesis. Education levels of the farmers may influence chances

of implementing and/or adopting the water harvesting techniques.

Low education levels of the interviewed respondents may

have significantly contributed to the low or non-adoption of water

harvesting techniques. This is because, education increases one

access to information and therefore creates awareness and contributes

to adoption of water harvesting systems. Chianu & Tsujii

[50], reported that farmers ‘educational achievement can increase

the probability of water harvesting technology adoption.

The results revealed that, a higher percentage of young aged

farmers (21-40 years) 48.4% respondents had adopted zai pits

as compared to older farmers (61 and above years) 6.5%- and

middle-aged farmers (21-40 years) 34.2%. In general, the results

showed that farmers in their middle ages recorded higher percentages

82.6% (21 – 40 years and 41 -60 years) as compared to

very young and older farmers who together also recorded 17.4%

(below 20 years and 61 and above years). These results could be

associated to the fact that, zai pit technique is labor intensive. According

to a study by [51] the age of the farmer is a significant

variable that can impact use of soil conservation technologies.

Generally, older farmers may be more conservative, less flexible

and more uncertain about the benefits of zai pits.

It was shown from the results that, majority of the farmers

(82.8%) depends on farming activities for survival and generation

of income with very few depending on business and government

work for income with percentages of 6.8% and 10.4% respectively.

The gap between the farmers who had adopted the technology

and the non-adopters was very small. According to [52], agricultural

activity is one of the many possible sources of employment

and income for farm households across the world. This perhaps

may be one of the reasons why adoption of the water harvesting

technologies is low (Table 2).

The studies revealed a great number of adopted

farmers of

zai pit technology joining farmers association with a percentage

of 92.3% as again 7.7% who are not part of farmers associations.

The number of non-adopter who are part of farmers associations

is also greater than those who are not members of associations

with percentages of 80.9% and 19.1 respectively. In a nutshell the

numbers of farmer both adopters and non-adopter who are members

of farmers association is greater than their counterparts who

are not members with percentages of 86.85 against 13.2%. The

results revealed a positive significant relationship between membership

of farmers association adoption ( χ 2 = 31.449 , p=0.005). This

could be the reason why a large number of farmers were recorded

to be adopters since the information about the technology may be

spread to them in the groups.

Considering the gap between farmers who have sloppy land

and those who do not have is relatively wide, with majority of

farmers who have adopter the technology has sloppy land (71.6%).

Adopted farmers without sloppy land recorded the least percentage

(28.4%) followed by non-adopter with sloppy land. In general,

most farmers in the study area have sloppy land (61.5) as compared

to farmers who don’t have sloppy land (38.5%). A positive

significant relationship was recorded between landscape (sloppy

land) and adoption of zai pit technology ( 2 χ = 8.712 , p=0.003). The

majority of adopters of the technology having sloppy land can be

attributed to the fact that zai pit technology is a measure of collection

of runoff rain [17].

Based on the results, both adopter and non-adopters of the

technology who have benefited from NGOs are greater than their

counterparts who have not benefited from any NGOs with percentages

of 74.0% as against 26.0%. Adopters recorder the highest

number of people who have benefited from NGOs (113) followed

by non-adopters (106). The external support provided by

NGOs to farmers had a significant and positive relationship with

zai pit technology adoption ( 2 χ = 23.289 , p=0.001). This suggests

that promotion by external organizations plays a significant role

in adoption of soil water management technologies as revealed by

[31] in his studies. This result is also in agreement with the work

of [53] who established a positive and significant relationship of

external service and adoption of rain water harvesting technology.

The results suggest majority of the adopters have formal title

to their lands (75.5%) with relatively fewer adopters not having

formal titles to their lands (24.5%). On the other hand, there was a

great number of non-adopter not having formal title to their lands

as compared to those having title to their lands with percentages

of 55.3% and 24.5% respectively. The result revealed a significant

relationship between farmers holding formal titles to their lands

and zai pit adoption ( 2 χ = 17.02 , p= 0.002).

Majority of the adopters were identified to be using improved

planting materials with very few of the adopters not using improved

planting materials with percentages of 71.0% as against

29.0%. In the case of the non-adopters too majority of the farmers

were using improved planting materials as compared to their

counterparts who were not using improving planting materials

having percentages of 69.5% and 30.5% respectively. In general,

it was revealed that majority of the farmers were using improved

planting materials as compared to those who were to using improved

planting materials (Table 3).

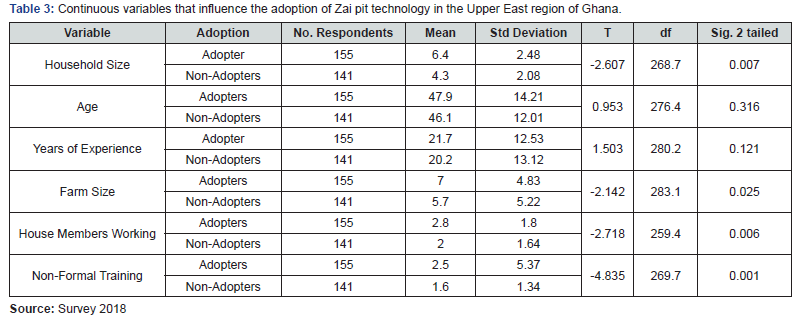

From the table above, the t-test result revealed a significant

difference between household adopters (6.4) and non-adopter

(4.3). Also, there was a significant difference (p= 0.006) that exist

between household members who work in the farm among the

adopters and the non-adopters. The average household for adopters

and non-adopter were 6.4 and 4.3 respectively. The results

showed that adopters had more labour sources compared to the

non- adopters with confirms the assertion [54] that large household

suggests more provision of labour particularly in the preparation

and maintenance of water harvesting technologies.

Moreover, the average age of the adopters was 47.9 years

whiles that of the non-adopter was 46.1 which suggest the farmers

in the study areas are in their youthful ages. Though the difference

in farmer’s age was not statistically significant, studies by

[55,56] revealed that older farmers are used to short term planning

thus are more reluctant to invest in soil conservation technologies

which take long before realizing the benefits. Contrary, [57]

in his studies reported that older farmers could be more aware

of soil infertility in their farms henceforth are more willing to try

new technologies that curtail the negative effects.

The total average farm size of adopter was highly than their

counterpart non-adopters with mean of 7.0 and 5.7 respectively.

There exists a significant difference at less than 5% probability

level. This result is in agreement with the studies [58] who find

out that farmers who had bigger farm size were likely to adopt

rain water harvesting techniques. Averagely, farmers who has adopted

the technology has received more non-formal training than

the non-adopters (2.5 and 1.6) respectively. This result shows that

non formal training plays a crucial role in the adoption of zai pit

technology. The result agrees with a similar-studies by [59] which

revealed significant and positive association between training and

adoption of water harvesting technologies (Table 4).

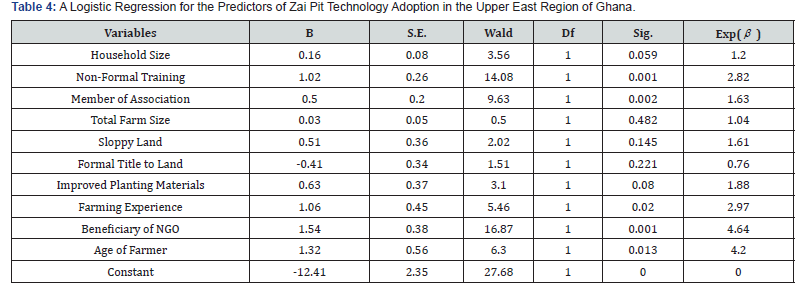

Table 4: A Logistic Regression for the Predictors of Zai Pit Technology Adoption in the Upper East Region of Ghana.

The logistic regression table revealed that, non-formal training

attended by farmers had a significant and positive influence

on adaptation of zai pit technology with exp ( β ) value of 2.820.

Farmer belonging to farmers groups and associations also had a

positive impact on adaptation of zai pit technology with exp ( β

) value of 1.63. The value of the exp ( β ) signifies that, for 1 unit

increase in the farmers joining or belonging to an association, the

probability of farmers adoption would increase by a factor of 1.63.

The result also shows that, there was a statistical significant relationship

between farmers farming experience and adaptation

of zai pit technology with exp ( β ) value of 2.97. Age of farmers

also had a positive impact on the adoption the zai pit technology

with exp ( β ) value of 4.20 which signifies a unit increase in age of

farmers, the probability of adaptation will increase by 4.420. The

results shows that beneficiary of NGOs was significant and had a

positive relationship with adoption of zai technology with exp ( β

) value of 4.46 which means a unit increase in the beneficiaries of

NGOs would render an increase in the probability of adaptation

by 4.46.

On the other hand, the logistic model results revealed that,

farm size, sloppy land, household size, used of improved planting

materials and formal title to farm lands were not significant

variables in the adaptation of the zai pit technology. Holding of

formal title to farming land had an insignificant negative effect on

adoption of the technology, however it was anticipated that farmers

who have title deeds are more likely to adopt the technology

as compared to those who don’t have the title deeds. Many smallholder

farmers who apply these technologies on leased land lose

the benefit of their investments because the owners withdraw the

land for their own use soon. Tenure insecurity explains farmers

‘unwillingness to invest effort in measures to improve soil conservation

and enhance fertility [60,61].

The results obtain from land size, family size sloppy land and

use of improved planting material (insignificant) is in contrast to

the studies of [62], who find out that the size of the farm was a

major a predictor in the adoption of soil water conservation measures

in Chile. The result was also in contrast with the studies finding

of [61,63] who also identified significant positive relationship

between land size and farmers decision to adopt soil conservation

and water harvesting techniques.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Out of the 296 farmers interviewed for the studies, 72.6%

representing 215 farmers were males and the remaining 27.4%

representing 81 farmers were females. The number of farmers

who were adopters were slightly higher than the number of

farmers who were non-adopters of the technology with percentages

of 52.4% and 47.6% (155 and 141) respectively. Majority

of the farmers (174 farmers) with a percentage of about 58.8%

had attain primary education out of which 94 respondents were

adopters and 80 respondents were non-adopters. Respondents

with tertiary education recorded the least number with 31 respondents

standing for 10.5% of which out of this number, 24 respondents

representing were adopters and 7 respondents were

non-adopters. In general, the results showed that farmers in their

middle ages recorded higher percentages 82.6% (21 – 40 years

and 41 -60 years) as compared to very young and older farmers

who together also recorded 17.4% (below 20 years and 61 and

above years). It was shown from the results that, majority of the

farmers (82.8%) depends on farming activities for survival and

generation of income with very few depending on business and

government work for income with percentages of 6.8% and 10.4%

respectively.

The results from the studies shows that

socio-demographic

characteristics of farmers such as, farmer‘s age, years of experience,

number of non-formal trainings, beneficiaries of NGOs, and

membership of associations, agents play an important role in

farmers adaptation of zai pits. On contrary variables like variables

like land size, sloppy land, household size, formal title to land and

used of improved planting materials were not significant variable

to farmer’s adaptation in the study area. The most common source

of information in the adoption of zai pits was non-government extension

agents. Majority of the farmers who had adopted zai pits

used animal manure as a soil fertility amendment.

Considering the verdicts from this study, the researcher, recommendations

that farmers should be encouraged to join farmer

groups or association and also attend non- formal training on agricultural

practices to improve adoption and utilization of zai pits.

Also, it is recommended that zai pit technology should be promoted

by the government and NGOs as a water harvesting technique

in the study area.

To know more about Journal of Agriculture Research- https://juniperpublishers.com/artoaj/index.php

To know more about open access journal publishers click on Juniper publishers

Comments

Post a Comment