Hop Biomass Composting Approach Impact on Compost Microbiological Properties- Juniper Publishers

Journal of Agriculture Research- Juniper Publishers

This sample study was used to take the snapshot of composts from hop biomass after harvest (stems and leaves of hop plants after hop cones harvest) and to start forming composting guidelines for hop growers to create quality compost for arable land. Each of three composting piles was prepared right after hop cones harvest in Sept. 2020 in a trapezoidal shape with a height of 2 m from 15 tonnes fresh biomass each. Differences among piles were in the size of the particles that the biomass was cut to, in coverage, in composting additives and in the number of pile turnings. We have reviewed the microbiological aspect composts after 7 months of composting. The microbial world of composted hop biomass solely (no other biomass added) is dominated by bacteria. In general, all composts lack diversity, which is main property of quality compost. The number of colonies forming units was in the range of expected, nevertheless, this unit has to be taken with precaution. PDA media stimulates growth of fungi and yeasts, therefore compost with effective microorganisms added at start, the smallest particles and foil cover after 1 month had the highest CFU on this media due to yeast fermentation. Fast changing conditions in soil demand fast adaptation of microbes that can only be tackled by diversity. The work on the topic will continue.

Keywords: Compost; Composting; Hop biomass after harvest; Humulus lupulus L; Microbiology; Diversity

Introduction

A primary objective of composting is to create efficient nutrient cycles in which nutrients from plant waste are effectively recycled into new plant biomass. During hop harvest, plants are cut and the whole aboveground biomass is taken from the fields. While cones are harvested, dried, and packed for brewing industry, stems and leaves (hop biomass after harvest) are left next to the harvest machine as a by-product. There are about 23,000 tonnes (15 tonnes/ha) of excess hop biomass (leaves and stems) produced in Slovenian hop fields each harvest season [1]. Although new ways of using hop biomass after harvest are being investigated, such as use for its antioxidant and antimicrobial activity for example [2], composting is still the most expecting way to use this biomass. Chemical composition of hop biomass is suitable for composting, especially when biodegradable twine is being used for hop support [3]. The ratio between carbon and nitrogen is 13: 1 when composting stems and leaves together and 23: 1 when composting only stems. Final compost (dw) contains about 3-4 % nitrogen, 0.3-0.4 % phosphorus, 1.0-2.5 % potassium, 35-43 % total organic carbon [4]. Microbes are responsible for the biochemical degradation of the organic litter and convert nutrients from organic to plant available, mineralized forms [5]. More than 90 % of all nutrients pass through the microbial biomass to higher trophic levels [6]. Many factors such as oxygen content, moisture, composition of the feed, pH, and temperature, affect microbes and consequently composting process. For that, compost chemical composition should be supplemented by microbiological overview [7]. Microbes are present in the environment. On average, 1 cm2 of plant leaf is covered by 106-107 bacteria [8], therefore the plant material itself present their source. If composting occurs on the soil, the soil also presents the reservoir of biological degraders which come to the compost pile. Composting induces high metabolic activities of many microorganisms (up to 1012 cells/g). The constantly changing conditions (temperature, pH, aeration, moisture, availability of substrates) results in stages of microbial consortia [9]. The initial decomposers are mesophilic organisms (bacteria and fungi). In the next stage, thermophilic organisms appear, especially actinomycetes, and the fungal populations decline. The final phase of composting is characterized by the development of a new mesophilic community; the actinomycetes remain and the fungi reappear along with cellulose-decomposing bacteria [10]. Soil compost amendments contribute to the general soil quality recovery and improvement of plant growing conditions [11] by providing numerous ecosystem services, including replenishment of soil carbon stocks, increase of microbial activity and biodiversity, and restoration of plant nutrition [12]. It has been demonstrated, that supplementing the soils with fungal or bacterial antagonists can reduce incidence of diseases in different crops [13-15]. There are various methods for assessing microbial picture of the compost; however, none of them is capable of perfect insight. Moreover, due to fast reproduction of bacteria in ideal environment, the population size is not as important as diversity and adaptability whereas in fungi, the size of organism can have greater impact [16]. In this study, we have reviewed the microbiological aspect of hop biomass composts after 7 months of composting. This insight will contribute to emerging guidelines for composting hop biomass after harvest solely, and to find the most suitable end use of the hop compost.

Material And Methods

Pile formation, weather conditions, process of composting and sampling

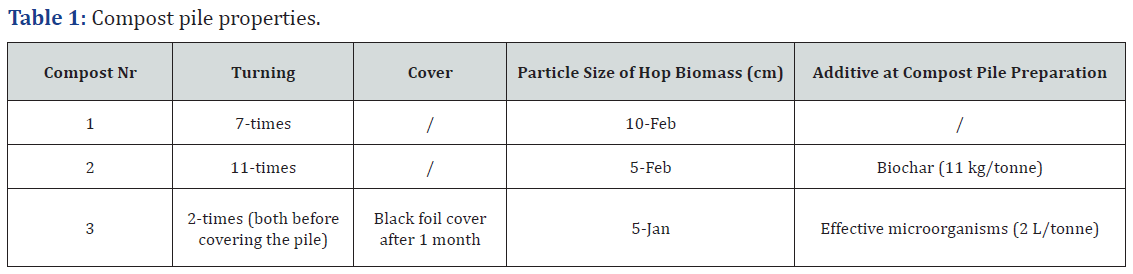

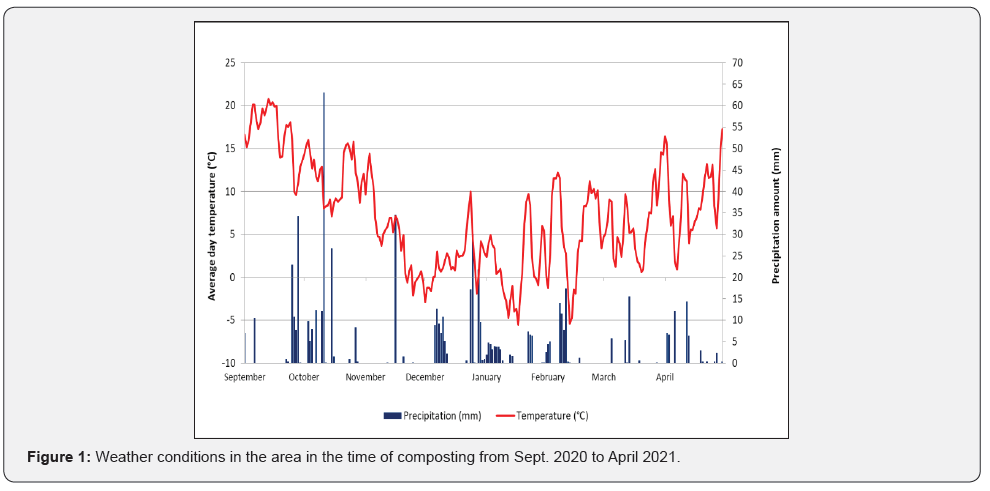

Composting experiment was performed between September 2020 and April 2021 in Lower Savinja Valley, Slovenia (Žalec; coordinates: 46.250997, 15.163939). Each of three composting piles was prepared right after hop cones harvest in September 2020 in a trapezoidal shape with a height of 2 m from hop biomass after harvest from 1 ha of hop field (approximately 15 tonnes each). Difference among piles was in the size of the particles that the biomass was cut to, two piles were uncovered all the season and one was covered after one month. There were no additives on the first compost pile, in the second we added biochar and in the third effective microorganisms (Table 1). Regular temperatures measurements were performed in the first two months and piles were turned when temperature was above 65°C; the number of needed turnings is presented in (Table 1). The piles were monitored during the degradation process and sampled for different analysis after 7 months of composting. Day precipitation amount and average daily temperatures in Žalec in the time of composting are presented in (Figure 1) [17]. There were a lot of rainy days in the last week of September and in the first half of October, with 9.7 mm average precipitation amount of rain per one day (Figure 2). In contrast, there was almost no rain from 17th October to 15th November. In December, there was much higher amount of precipitation on average in comparison to the 30-years average. Average daily temperatures were comparable to 30-years average only February was significantly warmer (Table 2).

Microscopy

Samples for microscopy were taken in triplicates, each from 4 different points in compost in April 2021. 1 ml of homogenized sample was placed in 15-ml tube and tab water was added to reach 5-ml mark. Tube was slowly inverted 30-times and left 1 min to settle. One drop of solution was placed on a slide and checked under light microscope for nematodes, flagellates, and ciliates, amoebas, bacteria, and fungi.

Total number of bacteria and fungi

Each sample was taken from 4 different points in compost. All samples were analyzed in duplicates. 50 g of sample was mixed with 200 ml of water. Ten-fold serial dilutions were prepared and applied to PDA and TSA plates. Plates were incubated for five days at room temperature before counted.

Microbial respiration

Microbial respiration was measured by Oxitop® system. Samples were taken in triplicates, each from 4 different points in compost. A fresh compost (20 g of dw) was placed in a jar with a cup of 10 ml 25-% NaOH and incubated for 5 days on 22°C. Pressure drop was measured every 24 min and was converted into O2 consumption by ideal gas law equation.

Results And Discussion

Microscopy

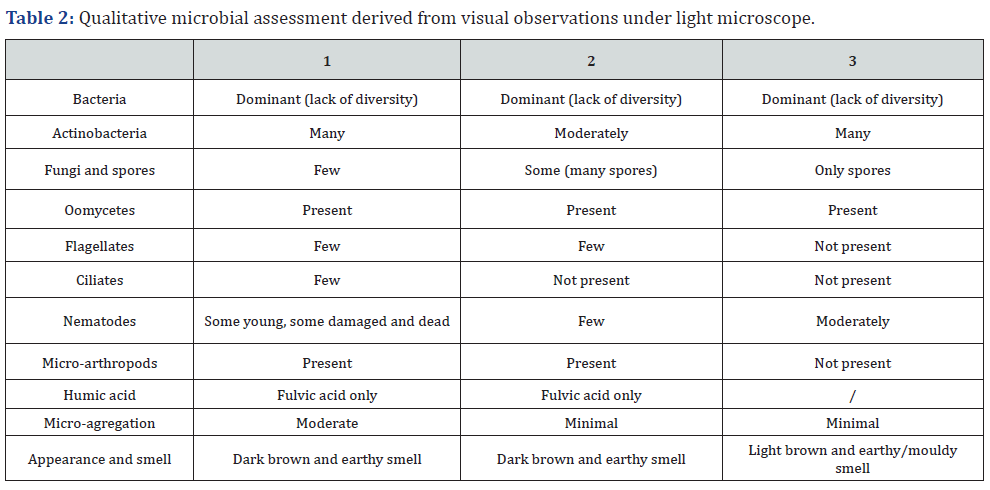

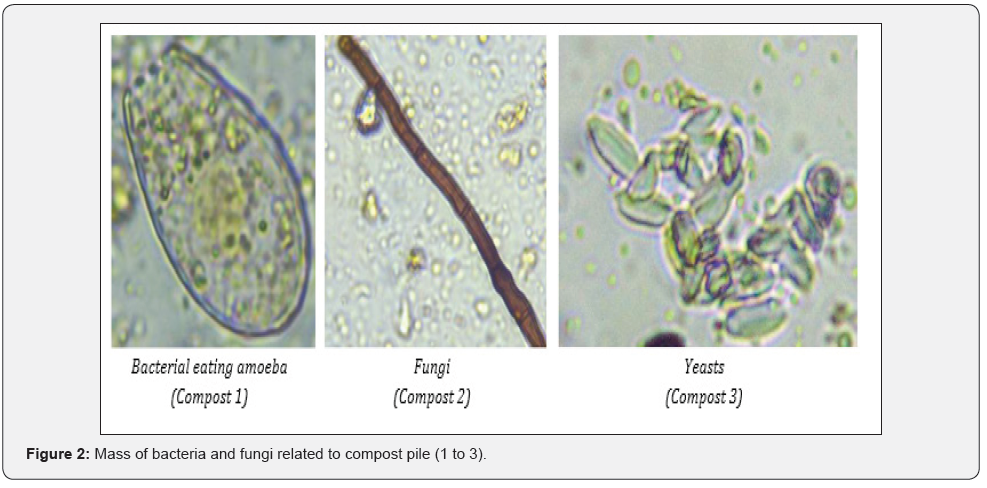

First notice of the compost under light microscope was bacterial predominance. Despite their abundance, the diversity of shape was poor. In general, the most biodiverse compost was compost 2, followed by compost 1 and compost 3. Composts 1 and 2 had many amoebae, while compost 3 lack these organisms. Bacteria are preyed upon by protozoa and nematodes, while fungi are preyed upon amoebae, nematodes, and micro-arthropods [18]. In soil, additional mineralization of microbial grazers is important when mineralization by microbiota is insufficient to meet plants requirements [19]. In general, composts lacked fungi that are important for breakdown of complex molecules and reabsorption of the nutrients [20]. Compost 2 had many spores that might activate when right conditions are met, while none was found in compost 3. When assessing fungal presence, the biomass ratio between bacteria and fungi must be calculated, as bacteria are single-celled organisms while fungi are multi-celled organisms that grow rapidly and in great lengths [20]. The biomass ratio between fungi and bacteria was 0 :1 as fungi hyphae were only found in traces. Fungi are aerobic organisms, therefore could not be found in compost 3 where anaerobic degradation or fermentation took place. Low presence of fungi in composts 1 and 2 can be linked to frequent turning of the compost that might have disturbed the hyphae growth. Bacteria are capable to grow and adapt more rapidly to changing environmental conditions as compost is than larger, more complex microorganisms like fungi. All composts contained Oomycetes that cause most of the soil-borne diseases [21]. Lack of microbial diversity can give opportunity to pathogens to attack plants and cause disease.

Total number of bacteria and fungi

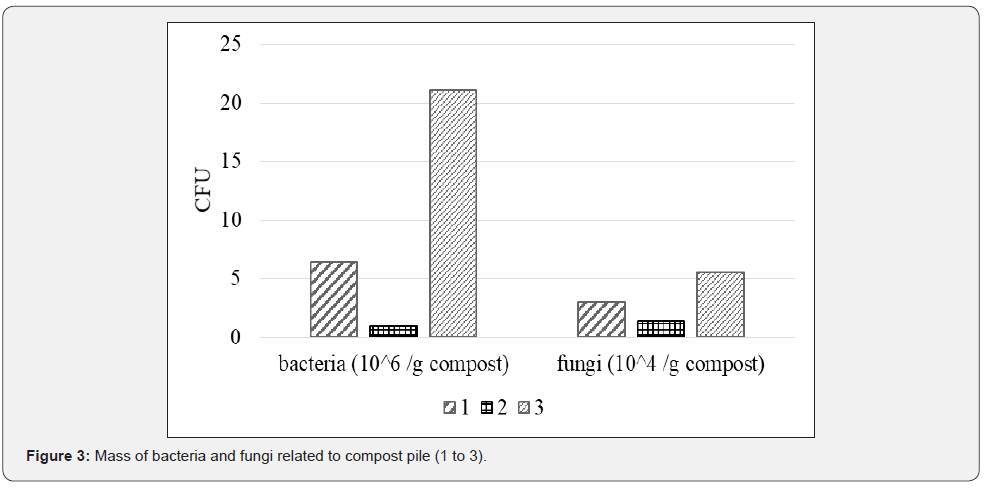

The most dominant populations of the composts were bacteria, with the most cultivable cells in compost 3 that also had the greatest number of fungi, but mostly due to presence of yeast as fermentation process took place in this pile (Figure 3). Compost 2 had the fewest number of bacteria and fungi. The problem, however, is that despite their viability, only a minor fraction of the microbes can be cultivated [22] have detected 21 x 106 CFU/g of green waste compost on TSA, like count of our compost 3 and [23] about 1 x 106 CFU per g of dw of compost from biowaste. Compost 3 had almost 20 times more bacteria than compost 2 and six times more than compost 1. Compost 3 had added effective microorganisms at the beginning of the process and had the lowest temperature during the degradation process, whereas compost 2 had the highest temperatures that might reduce bacterial populations. Compost 3 had the least diverse fungi population, as yeasts were dominant. Nevertheless, CFU is commonly used unit it cannot predict microbial effect in rhizosphere [16].

Microbial respiration

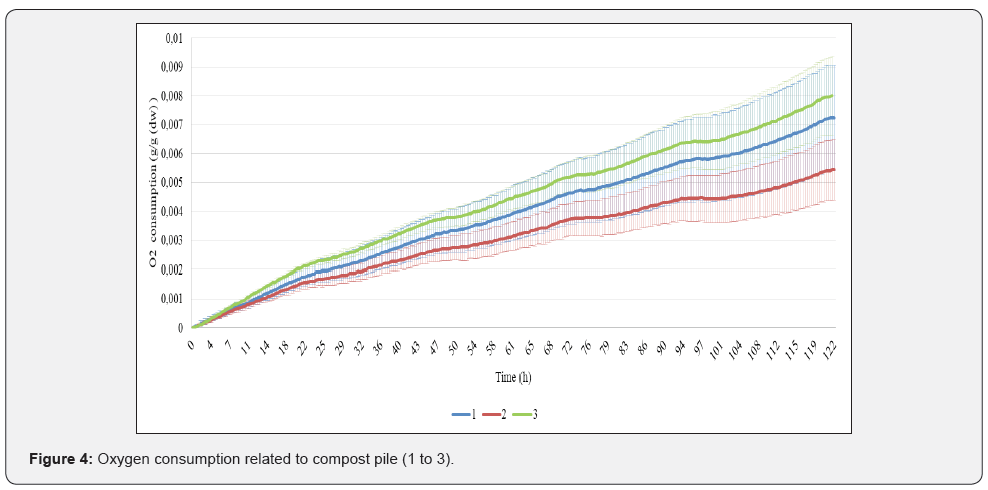

Compost that is no longer undergoing rapid decomposition and whose nutrients are bound is termed stable; unstable compost, in contrast, may either release nutrients into the soil due to further decomposition, or it may tie up nitrogen from the soil. Its microbiological component determines how the compost will perform as a soil inoculant and plant disease suppressant [9]. Oxygen consumption increased linearly in 5 days for all samples. Compost 1 had the highest variability between triplicates (CV=23 %), followed by compost 2 (CV=16,6 %) and compost 3 (CV=10.5 %). The highest oxygen consumption in 5 days was for compost 3 (7.6 mg O2/g dw), followed by compost 1 (7.2 mg O2/g dw) and the least in compost 2 (5.5 mg O2/g dw). Compost 2 and 3 statistically different, whereas compost 1 overlaps with both (Figure 4). Slovenian standard for 1st class compost is respiration bellow 15 mg O2/g dw in 4 days. It is suggested that for horticultural applications, <20 mg O2/kg compost dry solids /h is considered stable. For field applications, <100 mg O2/kg compost dry solids /h is considered sufficiently mature (Insam and De Bertoldi, 2007). By these parameters, tested composts are considered stable.

Conclusion

This sample study was used to take the snapshot of composts and to start forming composting guidelines for hop growers to create quality compost for arable land. Compost must provide suitable environment for plant growth as it is used as amendment to the soil. The microbial world of composted hop biomass solely (no other biomass added) is dominated by bacteria. Bacterial dominated soil correlates with historic origin of lower plants, while fungal dominated soil correlates with succession of higher plants. If these composts were used for hop plants, more fungi would be preferable. Part of mycelium was found only in compost 1 and 2. In general, all composts lack diversity, which is main property of quality compost. The number of colonies forming units was in the range of expected, nevertheless, this unit must be taken with precaution. PDA media stimulates growth of fungi and yeasts, therefore compost 3 had the highest CFU on this media due to yeast fermentation. Fast changing conditions in soil (heat, drought, moisture, lightness) demand fast adaptation of microbes that can only be tackled by diversity. Due to their fast reproduction, the number does not play such important role as their diversity. The work on the topic will continue.

To know more about open access journal publishers click on Juniper publishers

Comments

Post a Comment